In Antarctica’s McMurdo Dry Valleys, the ice doesn’t behave like the clean, silent thing people picture. In Taylor Valley, a tongue of the Taylor Glacier leaks a red stain that looks out of place against the blue-white ice. This place is Blood Falls.

The color is plain, backed by sampling and lab work, with iron turning to rust when it hits the air. The harder questions are where the water hides under all that ice, and why a sealed, salty pocket can still support life. That’s what makes Blood Falls worth the trouble.

Where Blood Falls Is, and How It Was First Recorded

Blood Falls sits at the end of Taylor Glacier in Taylor Valley, part of the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Victoria Land. This is one of the coldest deserts on Earth, a place where snow can vanish into the dry wind rather than melt.

The first widely cited record came from the 1911 Terra Nova Expedition. Geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor saw the red outflow and logged it. Early guesses pointed to red algae or other surface life, a reasonable idea at the time. Later testing didn’t support it. The red wasn’t a bloom on top of the ice. It was something carried up from inside the glacier, and it stayed a puzzle until researchers could sample the flow and trace its chemistry.

A Quick Timeline Readers Can Trust

- 1911: Taylor recorded the red outflow during Terra Nova work.

- 2003: Field studies tied the color to iron-rich brine, not algae.

- 2009: Peer-reviewed work reported living microbes in the brine system.

- 2023: A new analysis described iron-rich particles that help explain the color.

Why The Water is Red: A Rust Reaction, Not Blood

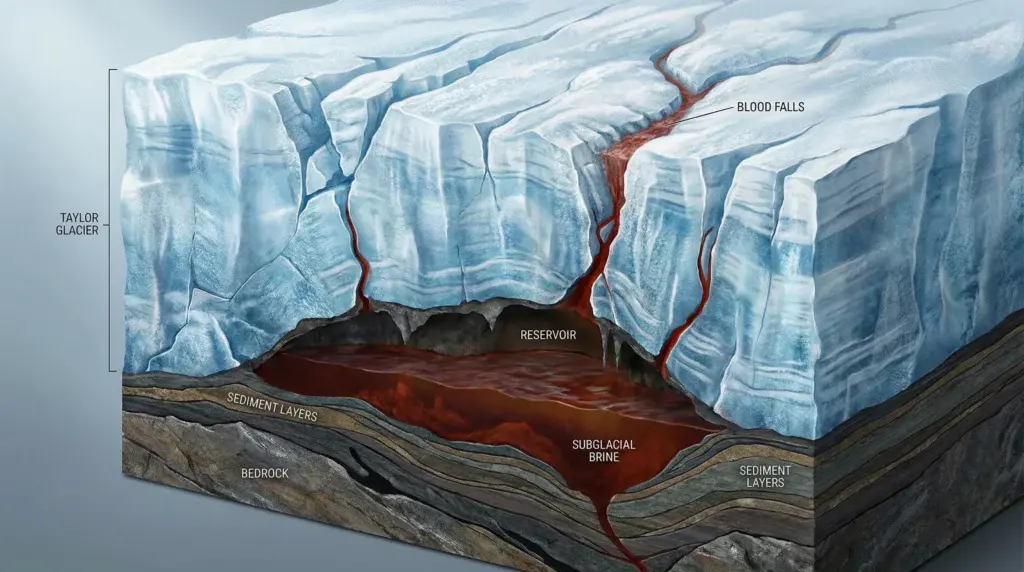

The “water” is really a hypersaline brine, loaded with dissolved salts and iron picked up from rock beneath the glacier. Salt lowers the freezing point, so this brine can stay liquid far below 32°F.

When the brine forces its way to the surface through cracks and channels, it meets oxygen. The dissolved iron reacts fast. It oxidizes, the same basic process that turns an old nail orange. That rust-colored iron compounds then stain the ice and snow around the outlet.

A 2023 report added a sharper detail: the red can be intensified by tiny iron-rich spheres formed during oxidation, mixed with other elements found in the brine. Johns Hopkins summarized that work in its overview of the modern explanation for why Blood Falls looks like a crime scene.

How Brine Can Stay Liquid Under So Much Ice

Researchers think the brine sits in a trapped reservoir under Taylor Glacier, linked to the surface by narrow pathways. High salt keeps it from freezing solid, pressure keeps it moving, and ice fractures give it routes upward. Radar studies have helped map parts of these internal pathways, without cutting the glacier open.

The Hidden Ecosystem Under Taylor Glacier

The brine is low in oxygen, yet it still hosts life. Genetic work has reported at least 17 microbial types in the system. These microbes don’t rely on sunlight. They can use chemical reactions involving sulfur and iron to generate energy, a survival strategy that fits the darkness beneath hundreds of meters of ice.

What’s still under debate is the full layout and behavior of the brine network: how big the reservoir is, how pathways shift, and how the chemistry changes across time.

Why Scientists Connect Blood Falls to Mars-Style Questions

Blood Falls doesn’t prove life exists elsewhere. It shows something simpler and more useful: cold, salty, lightless places can remain active. That helps teams build better tools and tests for looking for microbes on icy worlds.

Final Observation

Blood Falls may look violent, but the evidence points to chemical and pressure factors. Iron-rich brine rises from a buried reservoir, hits air, and rusts red on contact. Under that ice, microbes persist by using chemical energy rather than light. The system stays hard to reach, and the maps of its hidden plumbing are still getting sharper. That’s the real mystery, not the color.

Why is Blood Falls red?

The red color comes from iron-rich brine flowing out of Taylor Glacier. When the iron in the salty water hits air, it oxidizes, forming rust-colored compounds that stain the ice.

Is Blood Falls actually blood?

No. The color looks dramatic, but the waterfall is made of salty water loaded with iron. The red tone is a chemical reaction, not anything biological like blood.

Where is Blood Falls located?

Blood Falls is at the edge of Taylor Glacier in Taylor Valley, part of Antarctica’s McMurdo Dry Valleys, one of the coldest and driest deserts on Earth.

How can liquid water exist in Antarctica’s freezing temperatures?

The water is extremely salty, which lowers its freezing point. This allows the brine to stay liquid deep under the glacier even in subzero conditions.

Are there living organisms in Blood Falls?

Yes. Scientists have found microbes living in the oxygen-poor brine beneath the glacier. They survive using chemical reactions involving iron and sulfur instead of sunlight.

Why do scientists compare Blood Falls to Mars?

Blood Falls shows that life can survive in cold, dark, salty environments. That makes it a useful Earth example when studying how microbes might exist beneath the surface of icy planets or moons.

When was Blood Falls first discovered?

The red outflow was first recorded in 1911 by geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor during the Terra Nova Expedition to Antarctica.