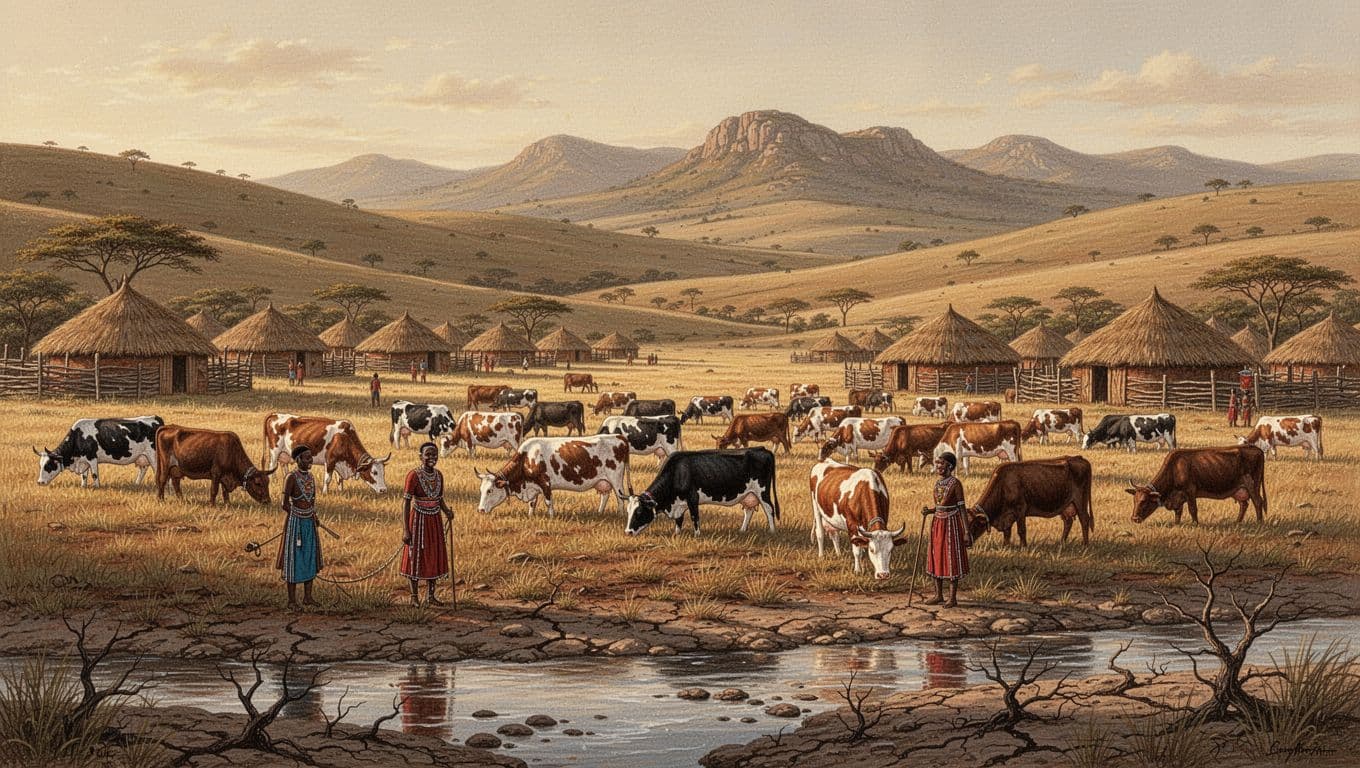

Eastern Cape, 1856. The frontier wars had just chewed through families and leaders. Colonial borders kept moving, and land that once felt settled started to feel temporary. At the same time, cattle herds struggled with a serious disease often described at the time as “lung sickness,” and fear spread faster than any virus.

In that pressure cooker, a teenage girl named Nongqawuse reported a message from the ancestors: destroy cattle and crops, then a renewed world would arrive. People heard what they needed to hear, a clean reset, a promise that loss would reverse.

The outcome is not in dispute. After the prophecy failed, famine followed. Historical accounts commonly report that about 40,000 Xhosa people died from starvation, after hundreds of thousands of cattle were slaughtered and fields were abandoned.

What Nongqawuse said would happen, and why people were ready to believe it

Nongqawuse was Xhosa, born around 1841 near the Gxarha River. By April 1856, she was about 15. She and a younger friend, Nombanda, went out to chase birds away from crops near the coast. When she returned, she said she had met ancestral spirits near a pool.

This did not travel as a loose rumor. Her uncle, Mhlakaza, took charge of it. He was a diviner and a religious figure with experience in the Cape Colony, where he had encountered Christianity. Back home, he acted as interpreter and organizer for Nongqawuse’s visions. Sources describe a key moment when Nongqawuse gave details about the spirits, including describing one as a man Mhlakaza recognized as his dead brother. That recognition mattered because it turned a story into something he treated as confirmed.

The belief itself had a clear shape. It was millenarian in the plain sense, a total reset of the world. The dead would return. New cattle would appear. Settlers would be swept away. The old suffering would end because the old world would end.

That message landed because the Xhosa were not speaking in theory. They were dealing with war grief, land pressure, political instability, and animal disease all at once. When a community loses control of the basics, food, land, safety, the idea of a hard break can sound like relief. It can even sound like discipline.

For a broader, accessible discussion of the social pressures behind the movement, see this University of Notre Dame essay on the Xhosa cattle killing, which ties belief to the realities on the ground.

The rules of the prophecy: kill the cattle, stop planting, rebuild everything

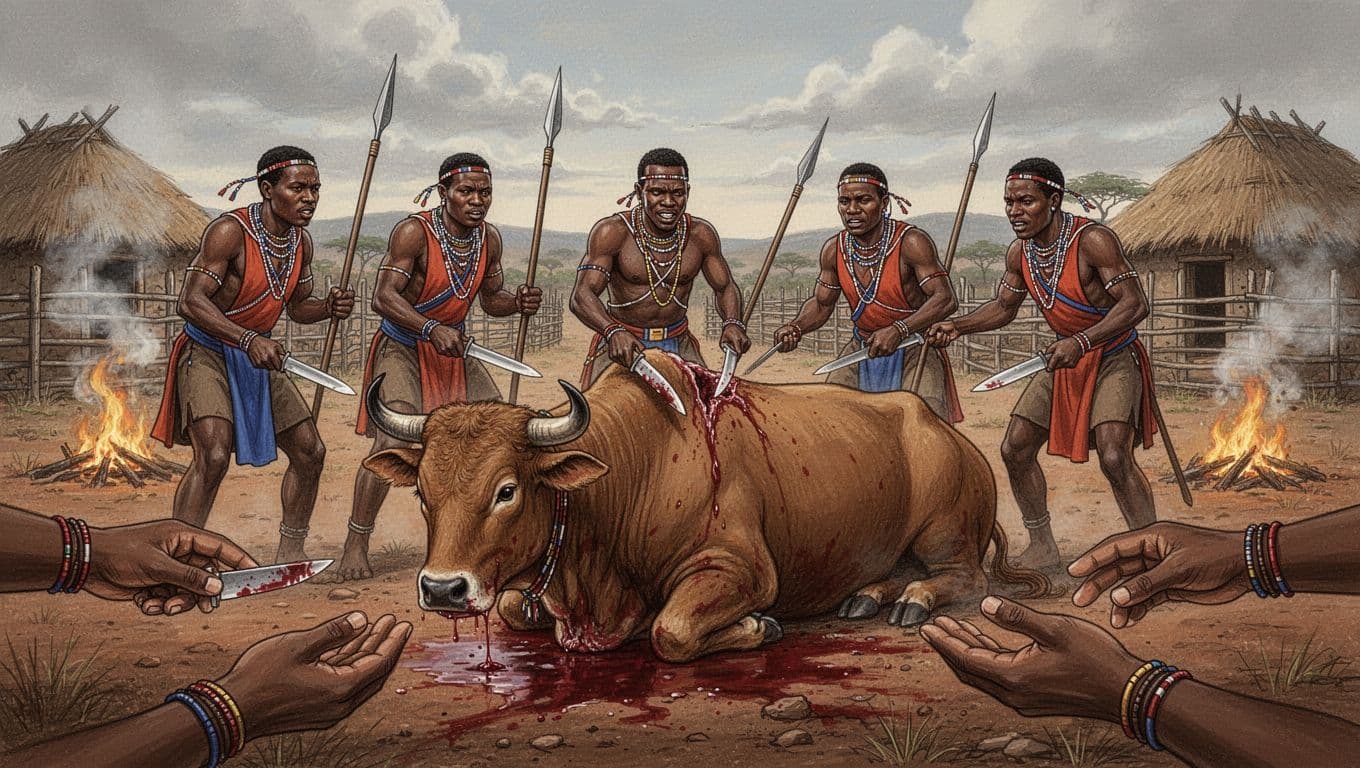

The prophecy came with conditions, not friendly advice. The core demand was simple and brutal: slaughter all living cattle, described as contaminated, and stop cultivation.

Then it stacked on more orders. People were told to destroy stored food, prepare new grain pits, build new houses, and raise new cattle enclosures. Some accounts also include instructions to make new milk sacks and weave doors with specific roots. Moral rules sat beside the practical ones: abandon witchcraft and sexual wrongdoing, including incest and adultery.

The logic ran in one direction. Obedience would bring renewal, and disobedience would block it.

Once the rules were framed as the price of salvation, backing out looked like betrayal, not caution.

The turning point: February 18, 1857, and the promise of a red sun

Prophecies survive longer when they have a date. Nongqawuse’s message did. February 18, 1857 became the day people waited for, with a sign attached: the sun would turn red.

As that date approached, expectations tightened. Leadership helped the message travel, too. Mhlakaza carried the prophecy to Chief Sarili (also spelled Kreli), and the movement spread far beyond one clan. Sources describe Sarili visiting the area connected to the visions and returning with renewed announcements, including a short countdown that raised the temperature in the final days. When leaders repeat a prophecy, it stops being private belief. It becomes public policy.

How the cattle killing spread, and how it collapsed into famine

Cattle were not a side asset in Xhosa society. They were food, bridewealth, status, and the working backbone of daily life. Crops added the other half of survival. So when people killed cattle and stopped planting, they did not just make a statement. They pulled out the floor.

The movement spread across the Xhosa nation, not only Sarili’s Gcaleka. Historians commonly estimate the slaughter in the hundreds of thousands, with many sources citing roughly 300,000 to 400,000 cattle killed. Exact totals vary by record and method, but the scale is consistently described as enormous.

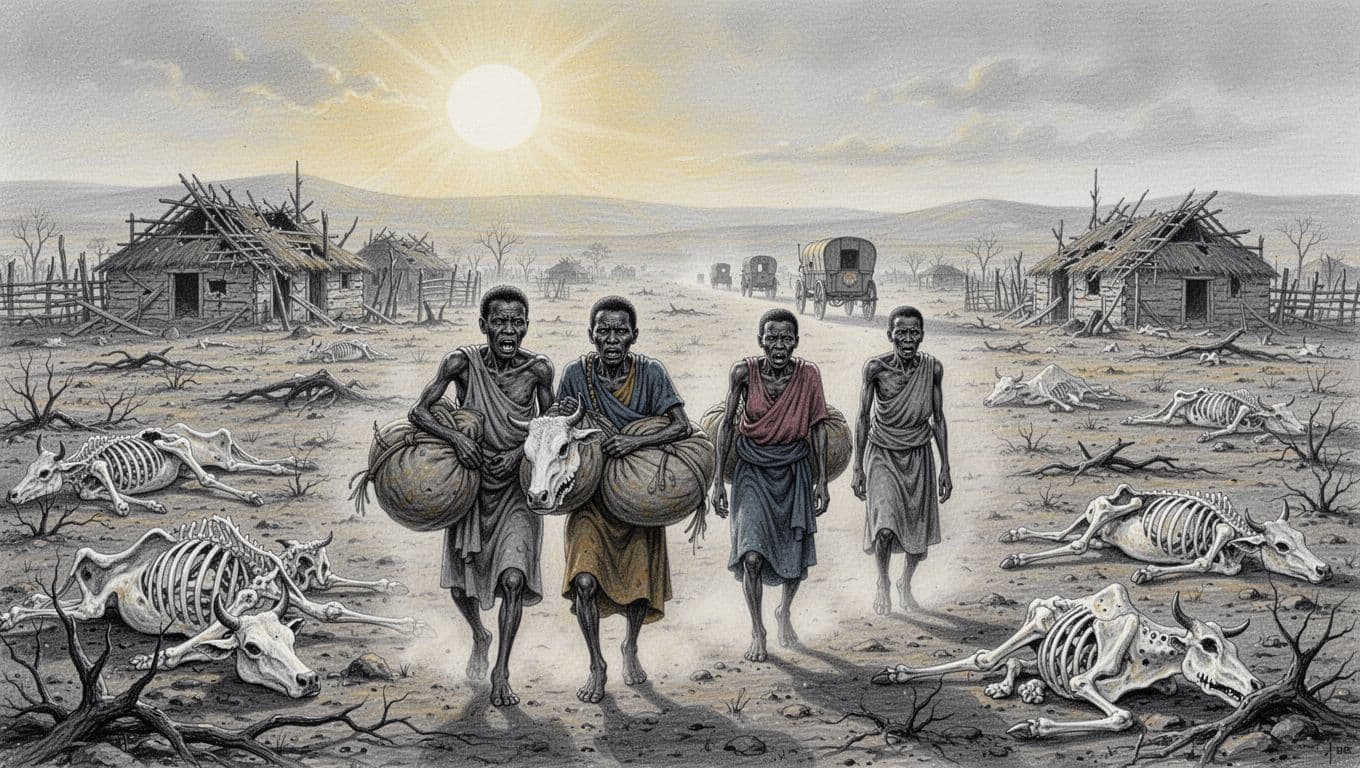

This matters because famine is not only about empty stomachs. It is about lost options. A healthy herd can buffer drought. Stored grain can cover a bad season. Trade can bridge gaps. The prophecy required people to burn those bridges.

When February 18 arrived and the world did not reset, the disaster did not begin. It was already in progress. By then, herds were gone, fields were neglected, and stores were shrinking. Hunger stopped being a fear and became a calendar.

The holdouts and the blame: the amagogotya who refused to comply

Not everyone obeyed. A minority, remembered as the amagogotya (often translated as “stingy ones”), held onto cattle and kept farming. In any mass movement, someone stays on the edge, and here the edge mattered.

After the prophecy failed, believers searched for a reason that did not require admitting the core claim was wrong. Some blamed the holdouts. The argument was simple: the promise would have arrived if everyone had complied.

That pattern shows up in many crises. Public sacrifice creates a trap. Once people have paid a terrible price, they feel pressure to defend the story that demanded it. Doubt becomes the enemy because doubt threatens meaning.

The death toll and the aftermath: what the records say happened next

The most repeated figure in historical summaries is grim and steady: about 40,000 deaths by starvation. Many accounts also describe a sharp population drop in the region during and after the famine, as hunger pushed people into colonial towns and labor markets, and as disease followed weakened bodies.

The movement did not drag on forever. It ended by early 1858, after the promised renewal failed to appear again and again.

Nongqawuse’s later life is partly documented. Colonial authorities questioned her, and she was held for a period. Records describe her living later on a farm in the Alexandria district. She died in 1898. Beyond that, reliable detail thins out, and the story becomes shaped by politics, memory, and blame.

What this tragedy still teaches us about fear, authority, and false certainty

The cattle killing persists in history because it was not just a bad call. It was a chain reaction. War and land loss made the future feel stolen. Cattle disease made wealth look cursed. Then authority figures repeated a message that demanded irreversible proof of loyalty.

How a community can talk itself into an irreversible choice

The mechanics are plain once you lay them out.

Shared fear narrowed choices. Public acts of commitment made backing out humiliating. Moral rules turned doubt into sin. Meanwhile, each step forced the next because the safety net got smaller every week.

People did not need to be foolish to get caught. They needed to be cornered.

What is known, what is disputed, and how to read this story responsibly

The prophecy, the slaughter, and the famine are well documented in colonial records, later scholarship, and Xhosa oral memory. Still, historians debate motive and responsibility. Some emphasize internal politics and spiritual tradition. Others point harder at colonial pressure, including claims that officials benefited from the collapse, or even encouraged it. Those arguments exist, but proof varies, and sweeping conspiracies often outrun the paper trail.

A responsible reading holds two truths at once: this was a real human disaster, and it unfolded inside a system already tilted by conquest.

When Desperation Masquerades as Salvation

Nongqawuse’s prophecy set a price: kill cattle, stop planting, and wait for renewal. Large numbers complied, leaders repeated the message, and the destruction spread. When the promised date passed, the reset never came. Famine did, and about 40,000 people died.

The hard part is the ending. These choices happened under pressure that most modern readers never face. History rarely hands out clean villains, or simple morals, and this story resists both. It leaves one question hanging: when fear closes in, what starts to feel like the only possible move?