Most people have a small, private list of “don’ts” and “just in case” habits. Knock on wood after you mention a good thing. Wear the same socks on game day. Skip the 13th floor button, even if you tell yourself it’s silly.

Research doesn’t support supernatural cause and effect in these moments. Still, superstition isn’t a sign of low intelligence. It’s a normal human response to uncertainty, pressure, and imperfect information.

This article explains why luck beliefs feel so real, even when we know better. First, how the brain builds cause and effect out of noise. Next, why stress and control needs push us toward rituals, and sometimes change performance. Finally, how culture and learning keep luck stories alive.

What a superstition is, and why the brain keeps making “cause and effect” out of noise

A superstition is a belief or ritual that links an action, object, or sign to good or bad luck. It’s pragmatic, it’s about outcomes. Wear the “lucky” shirt, avoid the “bad” number, say the phrase before the test.

That definition matters because it draws a boundary. Evidence-based claims can be tested, measured, and corrected. Superstitious claims clash with what science expects, yet they can still feel compelling in the moment.

Psychologists have described this tug as a split between what we endorse calmly and what we do under pressure. A person can think, “This doesn’t make sense,” and still cross their fingers anyway. The action isn’t proof that luck exists. It’s proof that the brain treats uncertainty like an itch, and rituals feel like scratching.

If you like reading about situations where people mistake pattern for cause (especially in eerie, unresolved cases), this theme shows up again and again in real unexplained phenomena puzzling scientists.

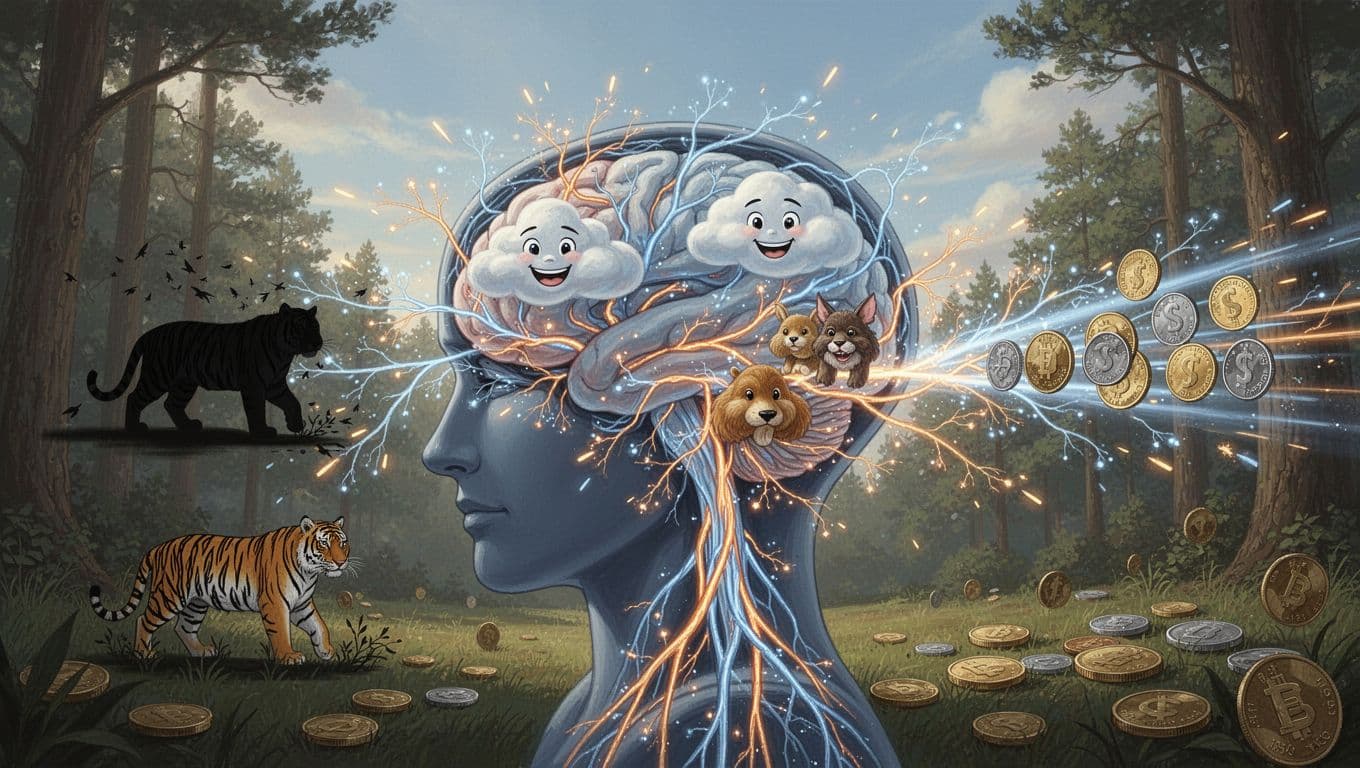

Pattern-spotting helps us survive, but it also creates false links

The brain is a pattern machine. That’s not a metaphor, it’s a survival skill. If the bushes move and you assume danger, you might be wrong. If you ignore it and you’re wrong, you might not get a second chance. So humans tend to accept false alarms because they cost less than missed threats.

This bias doesn’t stay in the forest. It follows us into everyday randomness.

A “jinx” can form after two rough mornings in a row. A charm can feel powerful because it “worked once.” A person flips three heads and starts to feel watched by fate. None of this proves luck. It explains why the mind prefers a story with a hook.

Why superstitions stick: confirmation bias and remembering the “hits”

Confirmation bias is simple: we notice the wins and forget the misses.

A sports fan wears a specific hat during two big victories. The hat becomes “the reason.” When the team loses, the fan blames the referee, injuries, weather, anything else. The hat’s failures fade fast, but its “hits” stay bright.

Agency also plays a role. People prefer explanations where actions matter. A world where outcomes happen at random feels cold. A world where a small ritual tilts the odds feels livable, even if it’s not true.

Uncertainty makes rituals feel calming, and sometimes that changes performance

Superstitions bloom when two things collide: the outcome matters a lot, and control feels low. Think auditions, surgeries, combat deployments, penalty kicks, job interviews, and final exams.

In those moments, rituals can calm the body and steady attention. That calm can change how we perform, without any magic involved.

Researchers have shown that “good luck” cues can improve results on certain tasks. In a well-known 2010 set of experiments published in Psychological Science, participants performed better when they believed an object or phrase brought luck. The consistent explanation was psychological, not supernatural: the luck cue increased self-efficacy, or the belief that “I can do this,” which then improved persistence and focus.

A broader look at how luck beliefs relate to thinking and well-being appears in an open-access study on luck beliefs and causal attributions.

The illusion of control: what rituals give us in high-stakes moments

Behavioral scientists, including writers and researchers like Stuart Vyse, have pointed out a repeating pattern: superstitions show up when people care deeply about an outcome but can’t guarantee it. That’s why athletes develop routines. It’s why some clinicians keep tiny habits before a procedure. It’s why a test-taker sharpens the same pencil twice.

Many of these habits are low-cost and private. No one needs to know you tapped the doorway three times. That privacy protects the belief from social pushback, so it can last for years.

The comfort is real. The cause is not. A ritual can lower anxiety, which helps attention stay steady. As a result, the person makes fewer careless errors. That is a normal pathway, similar to a placebo effect, and it doesn’t require luck to exist.

A charm doesn’t have to change the world to change your behavior. Sometimes it only has to change your breathing.

When “lucky” becomes risky: anxiety loops, gambling, and OCD look-alikes

The line gets crossed when superstition stops being flexible.

If a person believes something bad will happen unless the ritual is done perfectly, the ritual can feed anxiety instead of easing it. Some people start avoiding places, numbers, and ordinary choices. Others feel trapped in repeating behaviors. This can resemble compulsions, although only a clinician can assess what’s going on.

Gambling is another clear danger zone. Luck beliefs can keep people at the table longer than they planned. Games of chance stay games of chance, even when a “hot streak” feels personal. In that setting, superstition can turn into expensive decision-making.

Why cultures teach luck stories, and why they can still feel meaningful

Superstitions don’t spread only because individuals invent them. Families teach them. Teams pass them around. Movies and headlines refresh them. Over time, a small rule becomes a shared reflex.

Surveys in the US have repeatedly found that many people describe themselves as at least a little superstitious, even if they disagree on which ones matter. That mix makes sense. Specific beliefs change by region, religion, and family history, yet the underlying need stays constant.

Some practices also carry meaning, even when people don’t treat them as literal forces. Communal rituals can create belonging, and some studies link a sense of divine involvement with reported meaning in life. That doesn’t prove a supernatural mechanism. It shows how humans use shared symbols to feel oriented in the world.

For another example of how stories travel through communities and become “sticky,” the history of the Bigfoot legend is a clear case study in social learning, repetition, and cultural reinforcement.

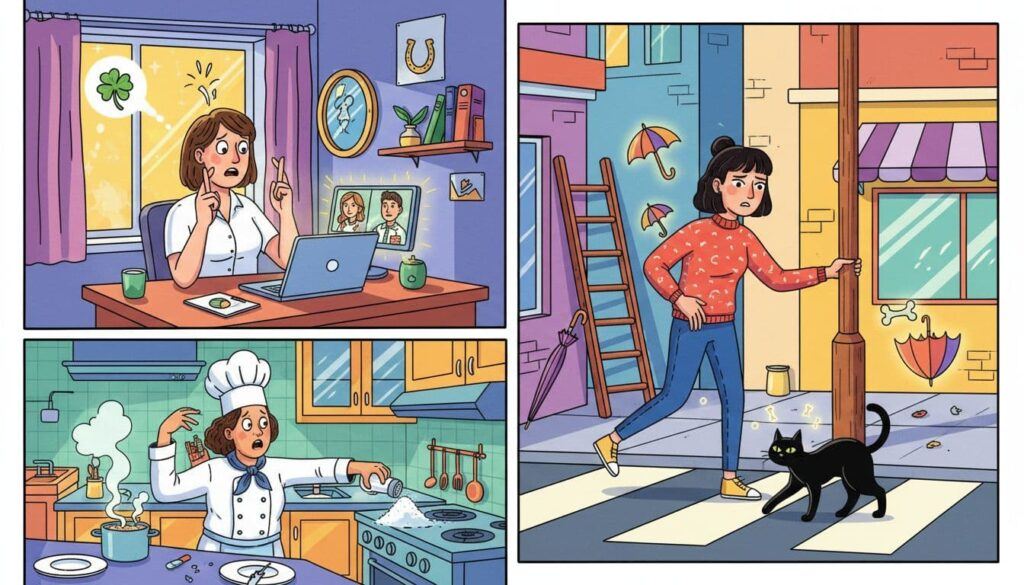

Social learning: we inherit black cats, lucky numbers, and “don’t do that” rules

Children absorb the emotional tone first. If a parent stiffens at a broken mirror, the child learns that the event matters. Later, the child learns the rule that explains the reaction.

Adults learn the same way, just with different sources. A teammate swears by a routine, and the routine spreads. A workplace treats a number as “bad,” and the building design quietly follows. Over time, the superstition becomes part of the setting, like furniture.

Ritual vs superstition: the key difference is the claim you’re making

A useful distinction is the claim behind the act.

If you light a candle because it calms you and connects you to family tradition, that’s a ritual function. If you claim the candle changes the physical world in a testable way, that’s closer to superstition.

People can hold meaning and evidence separately. It helps to ask, “What am I saying this does?” If the answer is “It helps me settle down,” that’s honest and often healthy. If the answer is “It guarantees safety,” that’s where fear can creep in.

Comfort, Control, and the Stories We Tell Ourselves

Superstitions persist for three grounded reasons. Brains search for patterns, even in noise. Stress makes control feel urgent, so rituals offer comfort. Culture then repeats those habits until they feel like common sense.

Psychology can explain the pull, and some studies show performance gains through confidence and self-efficacy. What research still doesn’t support is supernatural causality; no object or phrase has been shown to bend probability on its own.

A practical rule helps: if a ritual stays flexible, low-cost, and calming, it’s usually harmless. If it creates fear, costs real money, or starts running your decisions, step back. If it keeps escalating, talk with a qualified mental health professional.

Questions people ask about superstitions and luck

Quick answers pulled straight from the article’s ideas: pattern-finding, stress, control, and the way culture keeps luck rules alive.

What counts as a superstition?

A superstition links an action, object, or sign to good or bad outcomes through luck. The key part: the belief claims the link matters, even without evidence that the action can change probability.

Why does the brain see “cause and effect” in random events?

Pattern-spotting protects survival. False alarms cost less than missed danger, so the mind prefers a story with a hook. That same habit shows up in everyday life, where randomness still feels personal.

How does confirmation bias keep superstitions alive?

Wins get remembered. Misses get explained away. A lucky hat “worked” during a big game, so the brain saves that moment as proof and quietly discards the losses where the same hat did nothing.

Why do superstitions show up most under stress?

High stakes plus low control creates a craving for anything that feels stabilizing. Rituals lower anxiety and steady attention. Performance can improve from that calmer state, without any supernatural force involved.

Can “good luck” actually improve performance?

A luck cue can boost confidence and persistence. Better focus often follows. Results come from psychology (self-efficacy and reduced stress), not magic bending the odds.

What’s the difference between a ritual and a superstition?

The difference sits in the claim. A candle lit for calm or tradition stays a ritual. A candle said to guarantee safety or change probability turns into superstition.

When do superstitions become risky?

Risk shows up when the belief stops being flexible. Fear-driven rules, money-loss behaviors (gambling “hot streak” thinking), or rituals that start running daily decisions point to a problem worth taking seriously.

How can someone keep a harmless ritual from turning into a problem?

Keep the ritual cheap, optional, and easy to skip. Test one “no-ritual” day on purpose. If anxiety spikes or life starts shrinking around the rule, a conversation with a qualified mental health professional can help.