The Mundaneum: A Paper Internet in the 1890s

Most people think the internet began in the 1960s.

That is true in a technical sense. The protocols, packet switching, computers, and cables all came much later than the 1800s. But the deeper idea behind the internet is older than most of us think.

The internet is not only a network of machines. It is a system for finding knowledge.

That goal, organizing the world’s information so anyone can retrieve it quickly, showed up before the web, before search engines, and even before electronic screens became common. In the 1890s, a Belgian visionary named Paul Otlet began building something that looks strange at first glance but feels familiar once you understand it.

It was not digital. It was not online.

But it was a real attempt to create a global knowledge system, built on indexing, classification, and the belief that information should be accessible, organized, and connected.

In other words, Otlet was trying to build a paper internet.

What Was the Mundaneum?

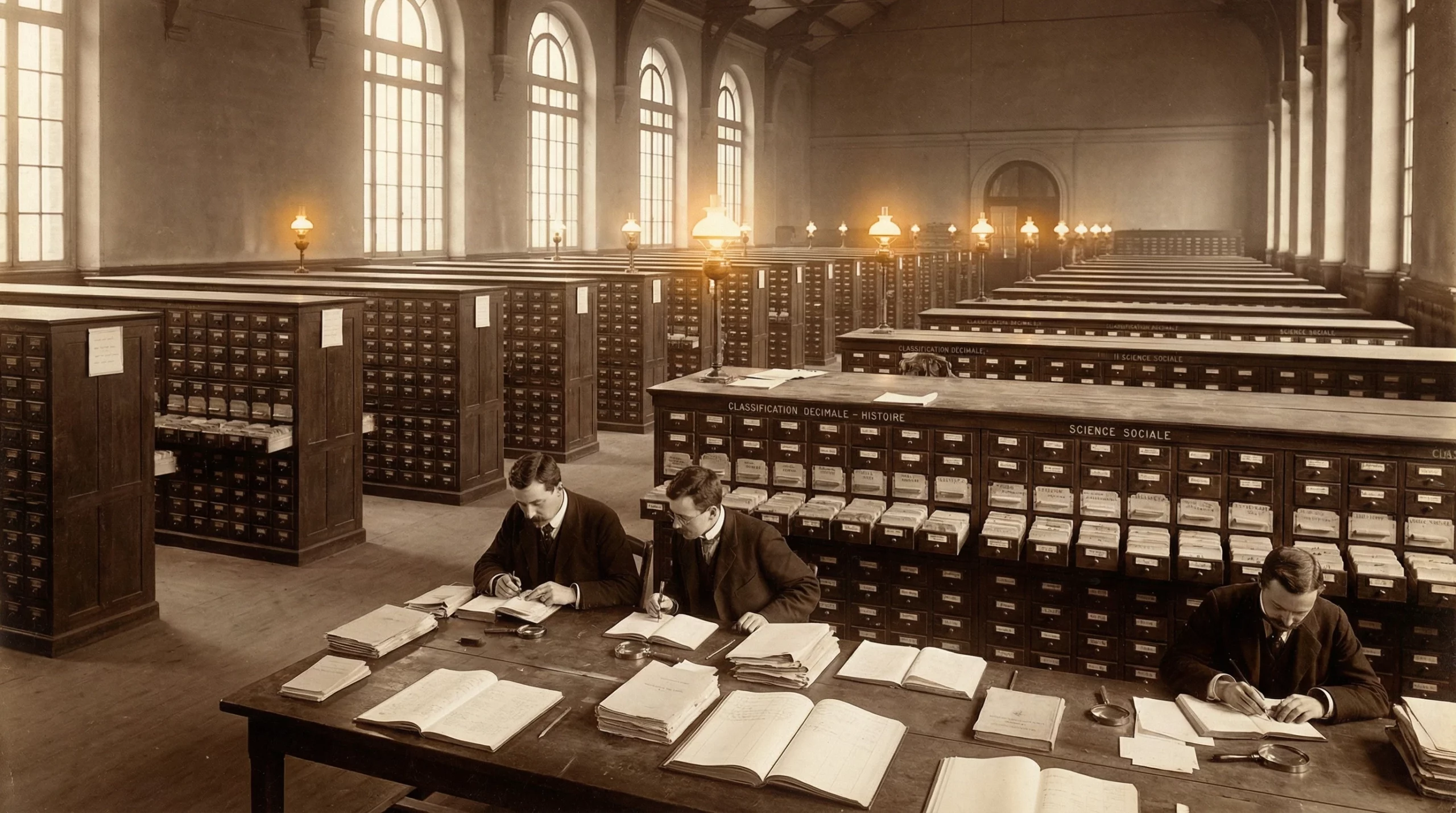

A “paper internet” built from index cards

The word Mundaneum sounds like a fantasy location. In reality, it was a documentation and knowledge organization project that aimed to gather and classify information from around the world.

The most famous piece of the Mundaneum story is the catalog itself: millions of entries stored on index cards, arranged in a structured classification system.

If you only hear “index cards,” it sounds small. It was not. The scale was the point.

Why the Mundaneum was more than a library

Otlet and his team wanted a single place where the world’s knowledge could be mapped, sorted, and searched.

Think of the Mundaneum as a physical search index.

Not the content itself. The index.

That is why it is such a strong “before the internet” story. Search engines are not mainly about storing pages. They are about creating an index that helps you discover and retrieve what matters.

Otlet was doing the same job, with paper and people.

Paul Otlet in the 1890s (The Man Behind the Mundaneum)

Otlet’s goal: organize the world’s knowledge

Paul Otlet was Belgian. He trained as a lawyer, but his lasting work had little to do with courtrooms. His obsession was documentation: how knowledge is recorded, categorized, and shared.

Otlet was not working alone. One of his key collaborators was Henri La Fontaine. Together, they pushed a huge project to catalog the world’s published knowledge.

Their work started in the 1890s. A commonly cited milestone is 1895, when their documentation efforts became formalized at a larger scale.

Otlet’s premise was simple, but intense:

- Knowledge should be organized.

- Organization should be standardized.

- Standardized knowledge can be shared across borders.

- Shared knowledge can reduce ignorance and conflict.

You can disagree with the idealism, but the method is the interesting part. Otlet was not only dreaming. He was building systems.

Why this idea caught fire in the late 1800s

The late 1800s were noisy.

Books were being published at a rapid pace. Newspapers spread faster than ever. Scientific journals multiplied. New fields of study popped up, and older fields became more specialized.

Libraries could store books, but storing information is not the same as using it.

If you have a huge collection but no reliable way to find the right sources, you have a maze. You have a place where knowledge gets lost.

Most people blame the lack of information. Otlet saw the opposite problem. The world was creating more knowledge than it could organize.

Today, we call this information overload. Otlet lived through an early version of it. He focused on the bottleneck that still matters now: retrieval.

How do you find the right thing quickly when the pile gets too large to browse?

How the Mundaneum Worked Like a Search Engine

A modern search engine does a few things:

- Collects information

- Breaks it into structured signals

- Stores an index

- Returns relevant results when you ask a question

Otlet’s system followed a similar logic, even if the mechanics were different.

Indexing: turning books into findable entries

Instead of crawling websites, the Mundaneum gathered information from books, reports, and periodicals.

But the key move was treating each book as a single item you could read from start to finish. They aimed to extract and describe parts of knowledge in a way that could be retrieved later.

Classification: the rules that made searching possible

Otlet cared deeply about classification. If every library uses different labels, you cannot combine catalogs. If every country uses a different approach, knowledge stays fragmented.

He pushed structured systems that made cataloging consistent. That consistency is what makes retrieval possible at scale.

Queries and answers: an early “search results” workflow

In a library, the catalog is as important as the books.

Otlet’s index cards functioned like an external memory system. The card did not need to contain everything. It needed to contain enough structure to help you locate, compare, and connect.

People have described the Mundaneum’s service model as a kind of human-powered search desk. Someone asks a question, staff consult the index, and the system produces relevant references and responses.

This is not Google. But the pattern is easy to recognize:

Question in. Results out.

And because it ran on people, the results could include judgment and summarization, not just references.

Why People Say the Mundaneum Predicted the Internet

Otlet did not “invent the internet.” He did not. But it is also unfair to call his work unrelated. The Mundaneum aligns with several web-like principles.

Connected knowledge (early “links”)

The web is not just pages. It is the connections between pages. Otlet believed ideas should be connected across sources, not trapped inside single books.

Even if he was working with paper, the mental model is link-shaped.

Remote access as a guiding vision

Otlet argued that knowledge should not be limited to those who can visit a specific building. The dream was wider access, across distance. That is one of the most internet-like parts of the vision.

Again, this was not streaming web pages to home computers in 1895. But it was a push away from knowledge as a local artifact and toward knowledge as a system that people can reach.

A shared system, not a single book

The Mundaneum was about building a system that many people could use, extend, and maintain. That matters because the internet is not one product. It is an ecosystem of shared rules and shared access.

What the Mundaneum Did Not Predict (And Why That’s Important)

Not computers, not packet switching

A good “forgotten genius” story stays powerful when it stays honest.

Otlet did not outline packet switching. He did not describe TCP/IP. He did not invent the computer.

The difference between “internet” and “internet-like.”

So what did he actually predict?

He anticipated the importance of:

- large-scale indexing

- standard classification

- fast retrieval

- cross-referenced knowledge

- broader access to information

That is enough to make the story valuable. It is also enough to avoid the backlash that comes when readers feel tricked by a headline.

A strong post does not need the claim “he invented the internet.” It needs the claim “he chased the internet’s core purpose.”

Why the Mundaneum Didn’t Become the Web

The limits of paper, labor, and physical space

If the model was so smart, why didn’t it become the default global system?

The answer is boring but important: Otlet was early.

His system relied on:

- paper storage

- physical space

- human labor

- slow transmission of requests and responses

Those limits are not small. They shape everything.

When digital computing arrived, indexing and retrieval could be automated. Storage became cheap. Copies became perfect. Transmission became fast.

Otlet’s approach had the right direction, but it lacked the missing engine: digital infrastructure.

Timing, money, and political disruption

Big knowledge projects need stable institutions and stable funding. When politics and war disrupt society, massive documentation systems are vulnerable.

So the Mundaneum is not only a story about a visionary. It is also a story about timing and constraints.

The “World Brain” and Other Early Internet Predictions (Quick Context)

H.G. Wells and the “World Brain” (1930s)

You may have heard the phrase “World Brain” in discussions about early predictions about the internet.

That term is most associated with H.G. Wells, who promoted a “World Brain” concept in the 1930s. Wells imagined a shared global encyclopedia, updated and distributed, available to people everywhere.

Wells is worth a mention because he captured the popular imagination.

Mark Twain and the telelectroscope (1898)

Mark Twain also played with the idea of global connectedness through a fictional device. It is not the same kind of project as the Mundaneum, but it shows that the “connected world” idea was in the air.

If you include Twain, keep it short. This post is about Otlet’s real system.

Lessons From the Mundaneum for Bloggers and Creators

This story matters because it applies to blogging right now.

Most creators treat publishing as a job. Otlet would disagree.

Publishing is step one. The real job is helping people find the right thing at the right time.

Build your own index (topic hubs and internal links)

Build topic hubs. Create a few strong pages that organize your best posts around one theme. Treat them as your table of contents.

Add internal links with intent. Link to help the reader, not to game the algorithm. Point to the next step, the definition, the deeper guide, or the comparison.

Retrieval beats volume

More posts do not automatically help. Better structure helps.

If your content is organized, readers stay longer. They trust you more. They find the next piece faster.

Update and maintain your best work

Otlet’s system was meant to be maintained. That is how information stays useful. Your blog should work the same way.

Update old posts. Fix broken links. Improve intros. Add new internal links.

Search engines are trying to do what Otlet sought to do: surface useful knowledge quickly. If your site improves retrieval, you are helping that mission.

Conclusion: The Mundaneum’s Paper Internet Still Matters

The internet feels modern because the technology is modern. But the hunger behind it is old.

We want access. We want clarity. We want to search.

In the 1890s, Paul Otlet looked at a world drowning in information and decided the solution was not more publishing. The solution was a system.

His system was paper. Ours is digital.

But the goal is the same.

My One-line takeaway: Paul Otlet didn’t invent the internet, but he tried to solve the internet’s main problem decades early: how to organize the world’s information so people can actually find it.

FAQ: The Mundaneum, Paul Otlet, and the “Paper Internet”

What was the Mundaneum?

The Mundaneum was a large documentation and knowledge-organization project associated with Paul Otlet and his collaborators. It aimed to collect, classify, and index information from many sources so people could retrieve knowledge quickly.

Did Paul Otlet invent the internet?

No. Paul Otlet did not invent the internet’s technology, such as computers, packet switching, or TCP/IP. His work anticipated key ideas behind the web, including indexing, standard classification, and making knowledge easier to find.

Why do people call the Mundaneum a “paper internet”?

Because it functioned like a physical version of what search engines do online. It relied on structured indexing and classification, often using index cards, to help people locate relevant information from a massive body of published work.

When did the Mundaneum begin?

The project began in the 1890s. A commonly cited milestone is 1895, when Paul Otlet and Henri La Fontaine formalized major parts of their documentation effort. Different elements of the project expanded over time.

How is the Mundaneum similar to Google or Wikipedia?

The similarity lies in purpose, not technology. Like Google, the Mundaneum focused on indexing and retrieval. Like Wikipedia, it reflected a belief that knowledge could be organized, connected, and updated. Unlike both, it was entirely paper-based and depended on human labor.

What is the “World Brain,” and how does it relate to Otlet?

“World Brain” is most associated with H.G. Wells in the 1930s and described a shared global encyclopedia of knowledge. It relates to Otlet because both envisioned globally accessible knowledge, though Otlet’s work came earlier and focused on documentation systems rather than digital networks.