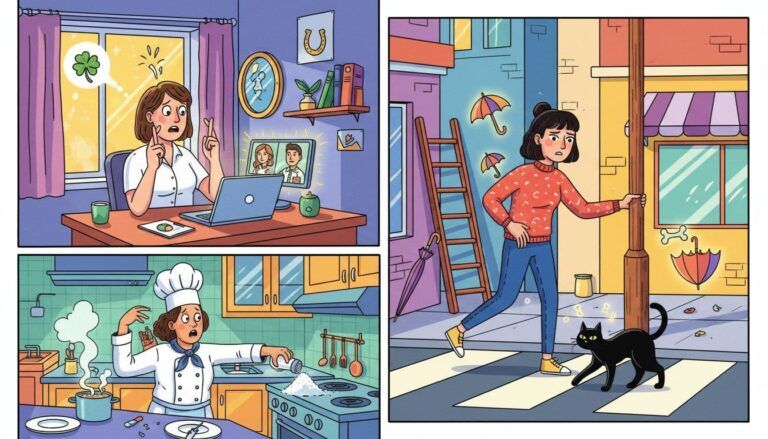

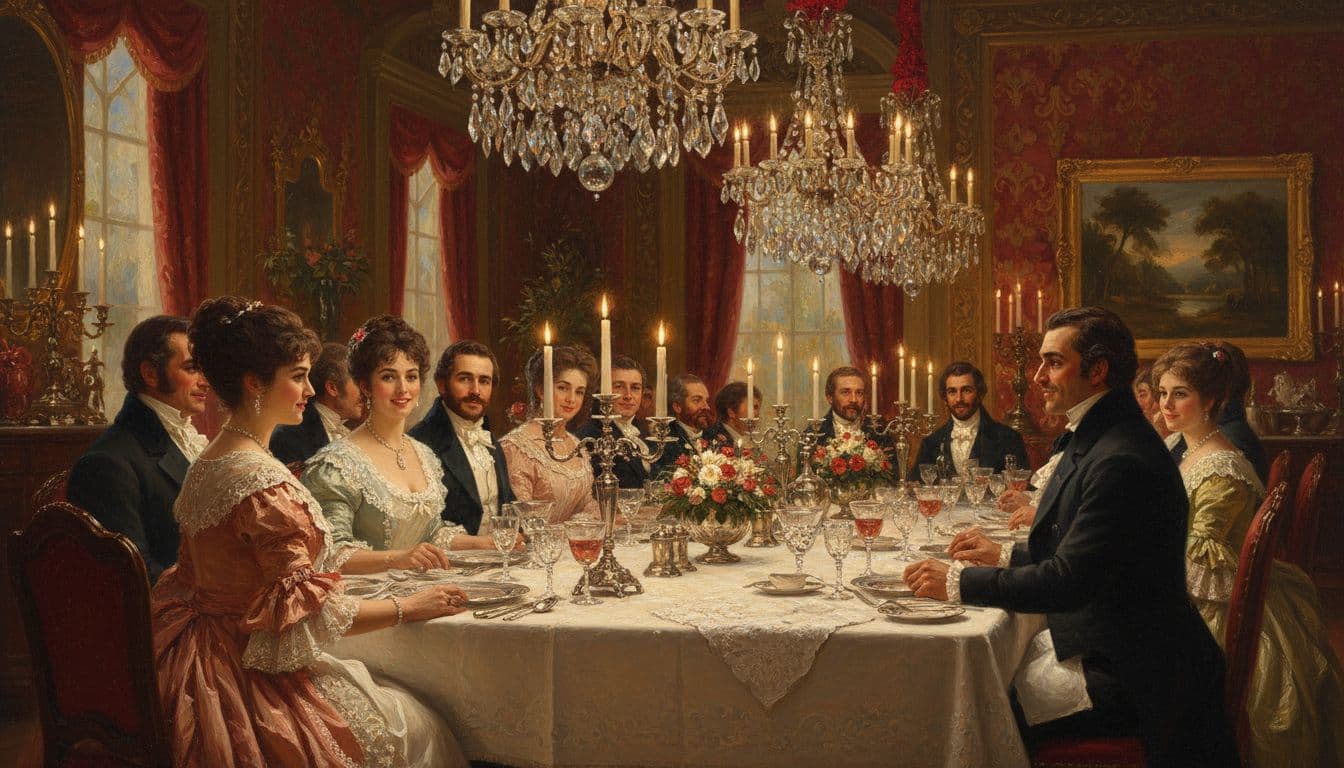

New Orleans in the early 1800s could look like a postcard on the surface, balcony railings curled like lace, gaslight glow, music spilling into the street. Inside certain homes, people ate well, laughed loudly, and built reputations on taste and manners.

That’s the setting for one of the city’s most documented scandals: Madame Delphine LaLaurie, a wealthy socialite whose public life was full of polished gatherings, while enslaved people in her household suffered extreme abuse. The core facts come from contemporary reporting and later historical work, and they’re grim without extra decoration.

This story matters because it shows how status can function like a shield, and how slavery’s legal structure created space for cruelty that neighbors could sense but rarely stop.

Delphine LaLaurie’s public mask in early 19th-century New Orleans

Marie Delphine Macarty, better known as Delphine LaLaurie, moved through New Orleans society with the ease of someone born into it. Through marriage and property, she became part of the city’s wealthy Creole elite. Her best-known address, 1140 Royal Street, was a place neighbors recognized, not just for its size, but for the social life it hosted.

Accounts from the period describe a woman who presented herself as respectable and controlled. That presentation mattered. In a slave society, appearances could decide who was believed, whose complaints were dismissed, and which rumors stayed only rumors.

And rumors did circulate. Neighbors and visitors reported unease about how enslaved people in the household were treated. Those suspicions weren’t enough to bring lasting consequences, partly because legal and social systems favored slaveholders. Enslaved people could not safely testify in the way free citizens could, and authorities often treated abuse as a private matter unless it became impossible to ignore.

That’s one of the quiet truths behind this case: the violence didn’t begin on the day the public learned about it. It had time to develop behind doors that wealth helped keep shut.

The April 10, 1834, fire that exposed the hidden rooms

The event that brought the story into the light was a fire on April 10, 1834. Reports from the time describe a blaze that began in the kitchen area. As people rushed to help, LaLaurie reportedly resisted giving rescuers access to parts of the house where enslaved people were confined. Bystanders and authorities broke in anyway.

What emerged next is the part most often retold, and it’s also the part with the strongest contemporaneous documentation: seven enslaved people were found in conditions showing severe, long-term abuse. One widely cited contemporary account, published in the New Orleans Bee the following day, described people confined and injured in ways consistent with prolonged torture. Other period descriptions mention starvation, visible wounds, and devices such as spiked iron collars used to restrict movement.

The fire also brought attention to the testimony of an enslaved cook who, in some retellings, is described as having chained herself to the stove in an attempt to escape further punishment. Versions of that detail vary, and not every later description can be traced cleanly to the earliest reporting. What is clear is that the fire led outsiders to a locked area, and that people were found inside in a state that shocked even a society accustomed to slavery’s everyday brutality.

Thousands of residents reportedly went to see the survivors afterward, when they were taken into public custody. That detail is easy to misread. It wasn’t only compassion that drew crowds. It was outrage, disbelief, and a harsh kind of proof-seeking, the need to witness with their own eyes what polite society had refused to confront.

Dinner parties above, torture below, how cruelty stayed hidden

The enduring horror of the Delphine LaLaurie case isn’t only the violence. It’s the contrast. This was a house associated with hospitality, style, and social climbing, while enslaved people were trapped in an upstairs space and treated as disposable.

It helps to name the mechanics that made that contrast possible:

- Social protection: Wealthy households had networks, friends, and reputations that slowed scrutiny.

- Control of space: Private rooms, locked quarters, and household hierarchy made concealment easier.

- Legal imbalance: Enslaved people had little recourse, and punishments could be framed as “discipline.”

- Public reluctance: Neighbors might suspect abuse, but many preferred not to provoke a powerful family.

There were also earlier warning signs. In 1833, an enslaved girl reportedly died after falling from the roof while trying to escape punishment. Authorities investigated, and LaLaurie’s enslaved people were removed, but historical accounts indicate she reacquired enslaved individuals later, allowing the same environment to continue. The pattern is familiar in many historical abuse cases: an intervention happens, but it’s temporary, and the person with power finds a way around it.

It’s also important to use language carefully here. Some popular versions of this story describe elaborate medical experiments or grotesque, highly specific acts of mutilation. Many of those claims appear in later folklore, not in the earliest press reports or official actions that we can reliably point to. The confirmed record already shows prolonged cruelty. Adding uncertain details doesn’t strengthen the truth; it blurs it.

Public outrage, a destroyed mansion, and a life that escaped punishment

Once the survivors were discovered, anger spread quickly. Contemporary descriptions say a mob attacked and heavily damaged the mansion, a rare moment when public fury overcame the usual deference to status. The house did not remain in ruins forever, but the destruction symbolized something immediate; the city was willing, at least briefly, to treat a wealthy woman as accountable.

LaLaurie, however, did not face a meaningful legal penalty. Accounts agree on the broad outcome: she and her family fled, leaving New Orleans during the chaos. Later reports place her in France. Modern historical summaries often give 1849 as the year of her death in Paris, although details of her later life are less well documented than the 1834 scandal itself.

Her story didn’t end with her disappearance. It became part of New Orleans folklore, and the address on Royal Street became a stop in the city’s ghost-tour economy. That afterlife in popular culture is worth acknowledging, but with a boundary: tourism tends to reshape events into entertainment. The real story isn’t a haunting; it’s what slavery allowed behind closed doors, and what it took for the public to finally see it.

One of the more influential modern retellings is a work of fiction; a character inspired by LaLaurie appears in American Horror Story: Coven. That portrayal keeps the name in circulation, but it also risks flattening history into a villain story. The historical record is worse in a quieter way. It shows a normal social world continuing, course by course, while people suffered upstairs.

A true story that has haunted New Orleans for nearly 200 years.

In the 1830s, socialite Delphine Lalaurie appeared flawless. After a fire in her mansion, a hidden attic revealed enslaved victims tortured in secret. This chilling account exposes her double life, her escape from justice, and the dark legacy that still follows her name.

Conclusion: What the Delphine LaLaurie case still asks of us

The Delphine LaLaurie scandal remains one of the best-known examples of documented abuse within American slavery, not because it was the only cruelty, but because a fire made it visible. It also shows how easily later legend can attach itself to real suffering, until the line between record and rumor gets hard to see.

If you take one thing from this, let it be this: the confirmed facts are enough, and they point back to a system where power often counted more than evidence. Read the earliest reporting when you can, notice what’s stated plainly, and treat the rest with caution. What other stories stayed hidden, simply because nothing ever burned?