On the night of 21 August 1986, a quiet crater lake in northwest Cameroon turned lethal. Lake Nyos released a dense cloud of carbon dioxide that slid out of the basin and into nearby valleys. By morning, 1,746 people were dead, along with thousands of cattle and other animals.

This was not a chemical attack, and it was not something paranormal. It was a natural gas disaster, tied to geology and a rare type of lake event. Investigators later confirmed the main killer was CO2, an everyday gas that becomes deadly when it pushes oxygen out of the air.

The story matters because the danger had no color, no flames, and little warning. What follows is what researchers and official investigations can support: what happened, why the gas stayed close to the ground, what scientists are sure about, and what changed afterward to cut the risk.

What happened at Lake Nyos, and what survivors actually reported

Lake Nyos sat in a steep volcanic crater, above small settlements connected by rough roads. During the night, something disturbed the lake, then a large amount of dissolved carbon dioxide came out of the deep water. The gas did not rise like smoke. Instead, it spilled over the rim area and moved downhill, filling low ground first.

Villages in the path included Nyos, Cha, and Subum. The pattern of death told its own story. Many people were found where they had been moments before. Some lay in beds, some on doorsteps, some along roads and paths. Families died together. Cattle and other livestock fell in large numbers, often in the same low areas.

Early on, the event confused everyone. There was no fire scene. There was no blast crater. Buildings largely stood. Trees were not charred. That lack of visible damage slowed understanding and fed rumors. Reports from survivors and later visitors sometimes mentioned a strange smell, a sound, or a mist, but those accounts did not line up cleanly across witnesses. Investigators treated those details cautiously because shock and timing can distort memory.

What did hold up under measurement was the gas itself. Teams took field readings and mapped where deaths occurred. The worst losses tracked the valleys and depressions. Medical findings also matched oxygen deprivation, not poisoning from a rare toxin. Carbon dioxide fit the physical facts because it can pool near the ground, especially in still night air.

The hard part about CO2 is that it can feel like nothing, right up to the moment it becomes unbreathable.

Why the death toll was so high, even though the gas was not “poison” in the usual sense

Carbon dioxide sits in the air all the time. Every breath out adds more of it. The problem comes when the concentration jumps high enough that oxygen drops too low. At that point, the body can fail fast.

High CO2 also pushes the urge to breathe harder. That sounds helpful, but it can backfire. Rapid breathing pulls in more bad air, and panic or confusion can set in. People can collapse before they understand what is happening.

Sleep made it worse. A person asleep does not read the room, smell a change, or decide to run. In a low-lying house, the gas can slide in and settle. The first sign may be dizziness, then loss of control, then nothing.

The science behind the “invisible cloud”: a limnic eruption in plain language

Scientists call the Lake Nyos event a limnic eruption. It is rare, but the mechanics are simple once you picture the lake as a sealed soda bottle.

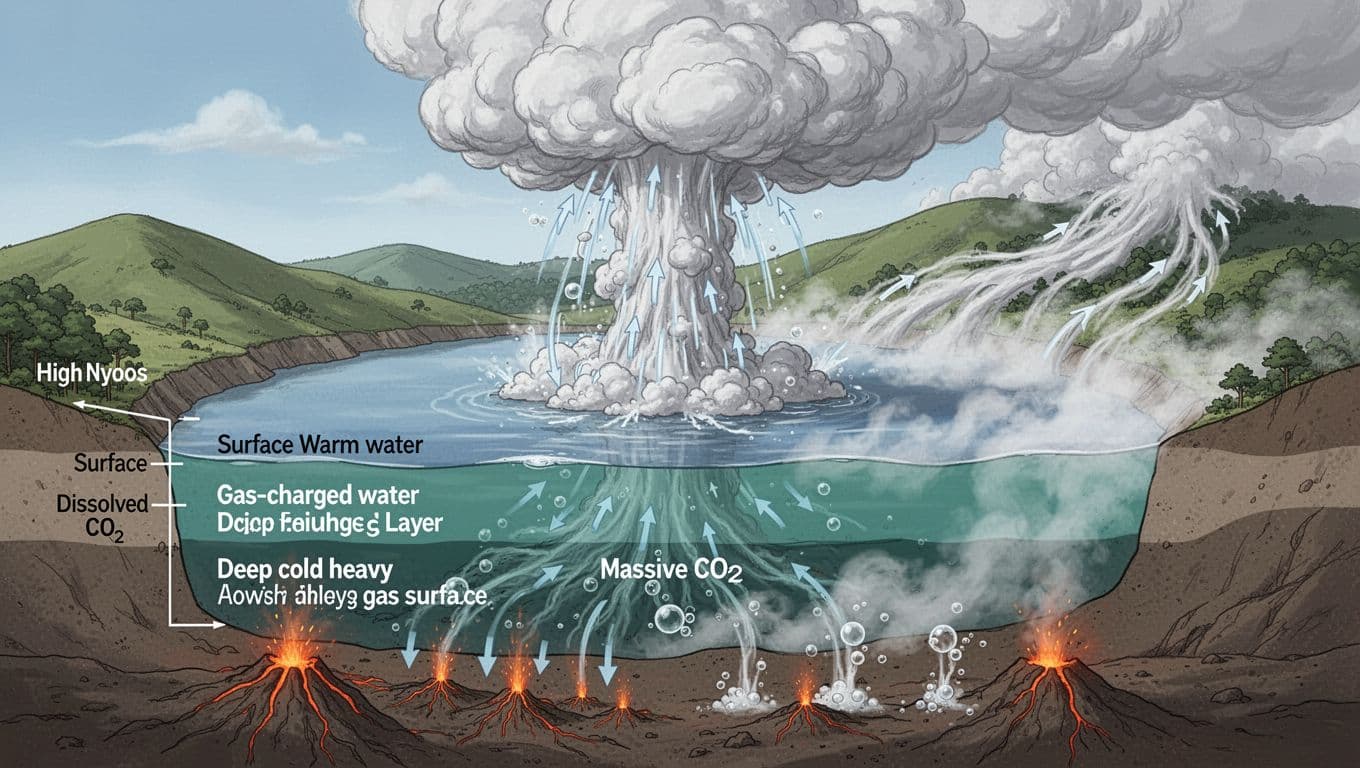

Deep under Lake Nyos, volcanic carbon dioxide seeped up through rock and into the bottom water. Pressure at depth kept that gas dissolved, the way pressure keeps bubbles trapped in a closed drink. Over time, the lake became layered. Warmer surface water stayed above, while colder deep water, loaded with CO2, stayed trapped below.

Then the balance broke. Something likely stirred the deep water enough to start a chain reaction. Once gas-charged water began rising, pressure dropped, bubbles formed, and the rising water became more buoyant. That made it rise faster. More pressure dropped. More gas came out. The process fed itself until a large volume of CO2 escaped in a short time.

Researchers agree on the core mechanism and on the central role of CO2. What they do not fully agree on is the exact trigger. Studies have discussed possibilities such as a small landslide into the lake, strong winds that mixed the water, or minor seismic shaking. The evidence does not point to one final answer, so scientists treat the trigger as unsettled.

The cloud stayed low because carbon dioxide is denser than normal air, especially when it comes out cold from deep water. It behaved less like smoke and more like a spill, flowing downhill and spreading along the valley floor.

Why people in low-lying areas were hit hardest

Topography decided who had a chance. Valleys, hollows, and enclosed rooms became traps because the gas collected where air circulation was weakest. Night conditions mattered too, since cooler, calmer air can keep layers from mixing.

Higher ground helped. People uphill or on ridges often avoided the worst concentrations. That matched the recovery maps, which showed heavy losses along drainage lines and in basin-like areas.

The same logic explains the livestock deaths. Animals in fields and pens on low ground took the hit first, while those on higher slopes had better odds.

What changed after Lake Nyos, and what we still do not fully know

After the deaths, Cameroon and international partners treated Lake Nyos as a long-term hazard site. Officials mapped risk zones, moved some communities away from the most exposed valleys, and set up monitoring to track lake conditions over time. That work also pulled attention to another Cameroon crater lake, Lake Monoun, where a smaller CO2 release in 1984 killed dozens. Nyos made it clear this was not a one-off story.

The big shift came with controlled degassing. Engineers installed pipes designed to vent CO2 slowly from the deep water, lowering the stored gas before it could build to dangerous levels again. The idea was direct: let the lake breathe on purpose, instead of waiting for it to erupt.

Still, limits remain. The equipment needs upkeep, and remote sites do not make maintenance easy. Relocation also carries a human cost because land, farming, and identity tie people to place.

Uncertainty also stays on the science side. Estimates of the exact gas volume released at Nyos vary by study, and the trigger remains debated. Researchers handle that the normal way, by publishing ranges, re-measuring the lake, and checking one another’s work.

Risk management does not require perfect certainty, it requires honest ranges and constant watching.

Degassing pipes: the simple idea that lowered the risk

The pipe reaches down into the deep layer where CO2 builds up. Once flow starts, deep water rises inside the pipe.

As that water rises, pressure drops. The dissolved gas turns into bubbles, like opening a shaken bottle.

Those bubbles make the column lighter, so it lifts faster. That keeps the siphon going, and the system can vent gas steadily instead of all at once.

The goal is not to drain the lake. It is to reduce the stored CO2 so a sudden release becomes far less likely.

When the Air Itself Becomes the Threat

Lake Nyos proved a blunt point: carbon dioxide can kill at scale when geology, lake chemistry, and valley shape line up. The gas was familiar, but the setting turned it into a night-long trap. After 1986, scientists and engineers changed how they monitored certain crater lakes and developed practical systems to reduce risk.

Some details remain argued over, especially the exact trigger and the exact amount of gas released. That debate does not change the core finding. A limnic eruption released CO2, the cloud stayed low, and controlled degassing became the clearest path to prevention. The danger was invisible; therefore, clear warnings and regular maintenance are essential.