Stories about Bigfoot, sometimes called Sasquatch, have circulated widely through folklore, eyewitness reports, and popular culture. My aim in sharing this is to provide background, highlight what’s reliably documented, and clarify a few points that tend to get lost in the noise. Although claims of wild, hairy giants in North America go back centuries, actual proof remains up for debate, and plenty of details have been muddied over time. Here’s what the historical record and credible research actually say about Bigfoot’s legend.

The Earliest Accounts of Large, Hairy Beings

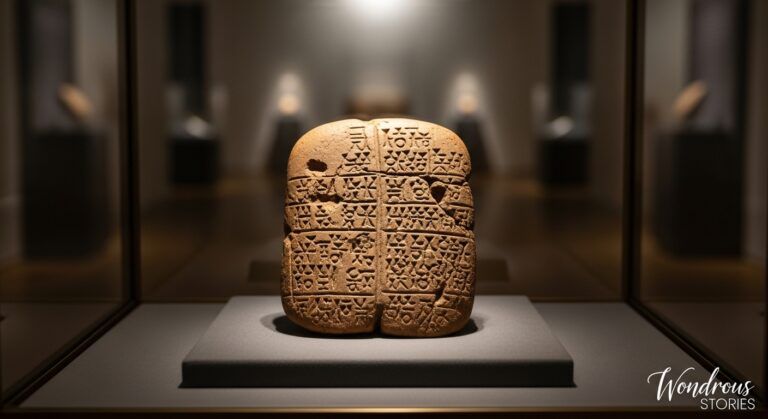

Bigfoot reports aren’t just a recent craze; they stretch farther back than many people expect. Documented accounts of wild, giantlike creatures appear in the oral histories of Native American groups living in densely forested regions of the Pacific Northwest and Canada. Translations of these stories, recorded by early anthropologists and ethnographers, note that tribes like the Lummi, Salish, and Spokane spoke about mysterious beings, sometimes called “Sasq’ets,” “Ts’emekwes,” or “Stiyaha,” who lived deep in the forests, avoided humans, and were known for their size and strength. (See Smithsonian Institution Anthropological Reports, 1907; The Indian Tribes of North America by John Swanton).

These accounts were passed down long before European settlers arrived, and they’re not exactly interchangeable with today’s Bigfoot sightings. Instead, tribal elders described the creatures as part of their living landscape: a curious, sometimes unnerving presence, but not a monster or media phenomenon. In fact, some traditions suggested that these beings were more spiritual or possessed supernatural qualities, serving as cautionary tales or explanations for the unknown noises and shadows in the woods. Over generations, these legends were woven into tribal identity, highlighting a unique relationship with the wilderness and its mysteries.

The Modern Sasquatch: Entering Western Records

Settlers in the 19th century began recording accounts that resemble the modern Bigfoot narrative. The word “Sasquatch” itself comes from J.W. Burns, a Canadian newspaper reporter, who collected and popularized local accounts from First Nations people living around Harrison Hot Springs, British Columbia, in the 1920s. Burns published articles in magazines such as Maclean’s in 1929, using “Sasquatch” as an anglicized version of “Sasq’ets.” (Burns’ original articles and clippings are in the British Columbia Archives.)

The word “Bigfoot” didn’t appear until 1958, after the Humboldt Times ran a newspaper feature highlighting enormous footprints found near Bluff Creek in Northern California. This sparked a new wave of public fascination, particularly after journalist Andrew Genzoli used the nickname “Bigfoot” in reporting on the casts and stories from loggers in the area. Later, one of the main witnesses, Ray Wallace, was revealed by his family to have fabricated footprints as a practical joke, which added a complicating layer to the already tangled story. (See Los Angeles Times, December 5, 2002.)

Key Evidence and the Growth of the Bigfoot Phenomenon

No discussion of Bigfoot’s legend is complete without examining what passes for evidence. Probably the most famous piece is the short film shot by Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin at Bluff Creek in 1967. This shaky footage, showing a large, bipedal, furry figure walking through a sandy creek bed, became the backbone of Bigfoot lore almost overnight. It still gets debated nearly every year, with some amateur researchers suggesting it’s an authentic encounter, while costume experts and skeptics argue it shows a person in a suit. To date, no independent analysis has provided a definitive answer, and the original film has undergone multiple rounds of review by wildlife experts, primatologists, and special effects professionals (for a summary, see Krantz, Grover S., and Meldrum, Jeff. “Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science,” 2006).

Other commonly cited evidence involves large footprints (sometimes measuring up to 24 inches long), partial hair samples, audio recordings of alleged vocalizations, and numerous eyewitness accounts. Scientific studies of these materials rarely support the claims. According to peer-reviewed work by Dr. Jeffrey Meldrum (Idaho State University) and others, most tracks examined so far either turn out to have identifiable hoax elements, plausible animal explanations, or just don’t contain enough unique features to prove anything unusual. Lab analyses on hair samples sent to wildlife and forensic labs usually identify them as belonging to known mammals, like bear, deer, or human, rather than something unknown (see Sykes et al., “Genetic Analysis of Hair Samples Attributed to Yetis and Other Anomalous Primates,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 2014).

Audio recordings of supposed Sasquatch howls and yelps are another cornerstone of Bigfoot folklore. Online databases are replete with clips, but when zoologists and audio experts review them, the sounds often align with known animal calls—sometimes owls, wolves, or even distorted human voices. Almost every line of purported evidence has been challenged or explained away through careful review, underscoring ongoing skepticism within the wider scientific community.

The Pacific Northwest: Why This Region?

The Pacific Northwest is often mentioned when people discuss Bigfoot. Dense forests, heavy rainfall, and large protected wilderness areas make this stretch between Northern California and British Columbia a natural backdrop for legends about things going unseen. Most verified Bigfoot reports originate from this region, as documented in databases such as the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization (BFRO) listings. If you look through logs and state wildlife records, the majority still cluster around rural and mountainous areas, where black bears and other large mammals are part of everyday life. This overlap provides practical reasons why people might misinterpret bear sightings or scattered prints as evidence of something more unusual.

Media attention also helped cement the image of Bigfoot in this setting. Tourism campaigns in places such as Willow Creek, California, and Harrison Hot Springs, BC, embraced the legend to attract visitors, establishing statues, museums, and themed events. Although modern sightings are disseminated online in seconds, the Pacific Northwest remains the primary “home” for most of these claims, likely because of its landscape and established lore. The sheer volume of untouched forest and misty valleys provides a sense of mystery, making it easy for both misidentification and mythmaking to take root.

Challenges in Sorting Fact from Folklore

The search for Bigfoot has always encountered problems with evidence. Scientific standards for confirming a new species are strict; biologists need to see a body or a bone, not just blurry photos, anecdotes, or stories passed through friends of friends. While honest people have reported strange encounters, and some researchers have tried to catalog reports systematically, hoaxes and inconsistent evidence are a significant part of Bigfoot’s history. Many of the original Bluff Creek tracks were determined by experts to show signs of tampering or artificial carving (see Krantz and Meldrum, “Sasquatch: Legend Meets Science,” chapters 2 and 4).

Over time, Bigfoot turned into more of a pop culture icon than a credible zoological mystery. TV shows, documentaries, and internet forums are loaded with eyewitness accounts, many of which can’t be independently verified or retraced. Major wildlife authorities, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Canada’s Ministry of Environment, do not list Bigfoot or Sasquatch as a recognized animal, and there are no museum specimens, fossils, or genetic sequences that add up to anything unknown.

Everyday Explanations: Bears, Hoaxes, and Misunderstandings

The most widely accepted explanations for reported Bigfoot sightings, supported by wildlife biologists, include misidentifications of black bears (especially those with mange), large humans, or intentionally fabricated hoaxes. Several case studies have documented incidents in which black bears standing upright on their hind legs were mistaken for something unusual from a distance (Williams, D., “Mammals of North America,” Smithsonian, 2002). Some track finds have later been traced to elaborate fakes, including wooden stampers or altered shoes.

Outright hoaxes have been part of the Bigfoot story since at least the 1950s. When Ray Wallace’s nephew and son admitted to creating fake tracks with wooden feet (LA Times, 2002), the effect echoed throughout cryptozoology circles. This doesn’t mean that every story is a deliberate prank; rather, the tradition of tricking both the public and hopeful seekers is well established in Bigfoot’s legacy. There have also been instances in which witnesses later recanted their accounts, clarifying that the events had been exaggerated or misunderstood.

Bigfoot in Modern Culture and Research

Despite the lack of physical proof, Bigfoot hasn’t faded away. Conferences, podcasts, television documentaries, and online forums fuel serious discussion and playful speculation alike. University-trained scientists such as Dr. Jeffrey Meldrum continue to study casts and reports, seeking to apply objective methods to the evidence that comes in. Most academic interest, though, leans toward analyzing the psychology of belief, the persistence of regional folklore, and what Bigfoot stories say about people’s relationship with wilderness and the unknown (see Dylan Thuras’ work in “Atlas Obscura,” 2016, and research papers by Brian Regal and others in “Skeptical Inquirer”).

Local economies, even whole towns, have benefited from embracing the legend as a quirky claim to fame, not unlike Roswell’s UFO history. Shops sell everything from bumper stickers to supposed “Sasquatch hair souvenirs.” Statues and roadside stops sustain tourism, even as the core mystery remains unresolved. In small towns near Bigfoot hotspots, festivals, guided walks, and museum tours have become an annual draw, attracting enthusiasts and casual visitors alike.

Frequently Asked Questions

Bigfoot: People Also Ask

Fast answers tied to the history, sources, and evidence covered in this article.

Is there any physical evidence for Bigfoot?

Where did the Bigfoot legend start?

What does the word Sasquatch mean?

When did the name Bigfoot first appear?

What is the Patterson–Gimlin film?

Have hair samples been tested?

Why do sightings sound so similar?

Why is the Pacific Northwest linked to Bigfoot?

Could bears explain many sightings?

How common are hoaxes?

Do Native traditions mention Bigfoot-like beings?

What would count as real proof?

Do wildlife agencies recognize Bigfoot?

Why does the legend persist?

What Remains Unresolved

No matter how many books, TV shows, or local attractions have popped up, there’s still no verified proof that a creature like Bigfoot roams North America. The only things that can be firmly attributed are the well-documented folklore, reports filed over decades, and the ongoing fascination with the boundaries of what’s possible. Scientists remain open to new evidence but require much more than anecdotes or blurry footage to alter current understanding. For now, that tension, between legend and science, hope and evidence, keeps the Bigfoot conversation going.