The Fermi Paradox Explained (Why the Galaxy Still Looks Quiet)

In 1950, physicist Enrico Fermi asked a blunt question that still lands with force: “Where is everybody?” He wasn’t writing science fiction. He was reacting to a simple mismatch between what seems likely and what we actually see.

The Milky Way is vast and old. Today, we also know that planets are common, including rocky worlds that sit in the right temperature range for liquid water. Yet we have no confirmed alien signals, probes, or other clear evidence of visiting or communicating civilizations.

That tension is the Fermi Paradox. It’s not proof that aliens don’t exist. It’s a question about missing evidence, and about which assumptions might be wrong. This post walks through what the paradox means, what we’ve searched so far, the best-known scientific explanations, and what research could turn debate into data.

What the Fermi Paradox means, and what it does not

At its core, the Fermi Paradox is a contrast:

- The galaxy has had ample time to produce life.

- There are an enormous number of stars.

- Many stars have planets.

- We still don’t see clear signs of a technological civilization beyond Earth.

The “paradox” part comes from how quickly people jump from those facts to a confident expectation of contact. That expectation often rests on extra assumptions that might not hold.

Here’s a helpful way to separate what’s solid from what’s inferred.

Fermi Paradox: Evidence vs Assumptions

A quick side-by-side view of what we can support strongly versus what we tend to assume.

| What we know (with substantial evidence) | What we often assume (less specific) |

|---|---|

| The Milky Way has hundreds of billions of stars. | Intelligent life is everyday once life begins. |

| Many stars host planets (confirmed by exoplanet surveys). | Civilizations expand far and fast. |

| Some planets are rocky and sit in temperate orbits. | Civilizations transmit signals that are easy to detect. |

| We have no confirmed, repeatable technosignature detection. | If a civilization exists, it leaves noticeable artifacts. |

This is where the “paradox” feeling comes from: strong facts on the left, tempting expectations on the right.

A lot of popular arguments use “big numbers” logic: with so many stars and so much time, some civilization should have reached us or at least become visible. That’s a reasonable guess, but it’s still a guess.

The basic idea: a big, old galaxy should be full of signs

Imagine a city the size of a continent, and it’s been inhabited for billions of years. You’d expect lights, noise, waste heat, structures, or traffic. Something.

The Milky Way is older than the solar system by billions of years. If even a small fraction of worlds produced long-lived, spacefaring societies, you might expect the galaxy to show evident traces. Researchers sometimes refer to the mismatch between expectations and observations as the Great Silence.

The key point is simple: we see a universe that looks natural and quiet, at least with the tools and searches we’ve done so far.

Common misunderstandings that confuse the debate

The Fermi Paradox gets messy fast because people mix different kinds of “evidence.”

A few common pitfalls:

- UFO claims aren’t the same as scientific confirmation. Anecdotes and unverified videos don’t give repeatable, instrument-backed proof of alien technology.

- “No signal found” doesn’t mean “no life exists.” It often means we haven’t looked enough, in the right ways, for long enough.

- Aliens might not use radio the way we do. Our strongest radio “leakage” period may be brief in historical terms.

- Our search coverage is thin. We’ve checked a tiny portion of the sky, frequencies, and time windows that could carry a signal.

If there’s a theme here, it’s limits. The paradox is real, but it’s built on incomplete information.

What we have searched so far, and why the silence is still possible

Photo by Pixabay

SETI-style searches have been running in one form or another since the 1960s, mainly focused on radio. More recently, some projects also search for optical or near-infrared laser pulses.

As of January 2026, there has been no confirmed SETI detection that repeats on command, survives follow-up checks, and can’t be explained by Earth-based interference or natural sources. That doesn’t mean the effort failed. It means the signal, if it exists, hasn’t shown up in the ways we can confirm.

What counts as a meaningful detection is strict for good reason. A “candidate” signal has to be re-observed, pinned to a sky location, and ruled out as interference. Many intriguing blips fade once you point the telescope back.

SETI in plain terms: listening for radio or laser clues

SETI searches look for patterns that nature rarely makes on its own, such as narrowband radio tones or repeating pulses that behave like engineered transmissions.

In simple terms, researchers:

- Point a telescope at a region of sky (often targeting nearby stars).

- Scan across frequency ranges.

- Flag signals that look unusual.

- Re-check them to see if they repeat and stay in the same sky position.

Optical SETI follows a similar logic, except it hunts for brief laser-like flashes or other unusual light patterns.

The hard part is that Earth is loud. Satellites, aircraft, ground transmitters, and even electronics can pollute the data. Sorting “maybe” from “real” takes patience and repeated observation.

Why “we found nothing” can still be true even if life is out there

Even if technological life is common, the silence can still make sense. Not as an excuse, but as a plain engineering and timing problem.

A few grounded reasons:

Signals fade with distance. Radio transmissions spread out. Unless a civilization aims a powerful beam at us, the signal can drop below our noise floor.

Civilizations may not broadcast for long. Humans have been “radio loud” for about a century. That’s a thin sliver of time.

We don’t monitor every target all the time. Many searches observe a star briefly, then move on. A short transmission can slip through.

We might be listening to the wrong channels. A society could use tight-beam communication, fiber-like local networks, or methods that don’t radiate much into space.

None of this proves aliens exist. It only shows why the absence of evidence is not yet a clean verdict.

The leading scientific explanations range from “rare life” to “hard to notice.”

There are dozens of proposed answers to the Fermi Paradox. Some focus on biology, some on sociology, some on detection limits. The safest way to think about them is in a few broad buckets.

Also, one caution that deserves to be said out loud: the monocultural fallacy. It’s easy to assume all alien societies behave the same way, expand the same way, and communicate the same way. That’s not something we can justify with evidence.

The Great Filter: one step on the path to intelligence might be improbable

The Great Filter idea says there may be a significant bottleneck between dead chemistry and a long-lived technological civilization. The path includes steps like:

- The origin of life

- complex cells

- multicellular life

- large brains and tool use

- stable, long-term technology

We don’t know which step is hardest. That uncertainty is the point.

The Great Filter has two unsettling interpretations:

- The filter is behind us. If the hard step happened early, maybe Earth got unusually lucky.

- The filter is ahead of us. If the hard step comes later, maybe many societies fail after gaining powerful technology.

Science can’t place the filter with confidence yet because we have a sample size of one. Finding even simple life elsewhere in the solar system, or strong biosignatures on exoplanets, would shift the odds and sharpen this debate.

Rare Earth: Maybe the right conditions are uncommon, even with many planets

A “habitable zone” means a planet could have surface temperatures that allow liquid water, given the right atmosphere. It doesn’t guarantee oceans, a stable climate, or long-term habitability.

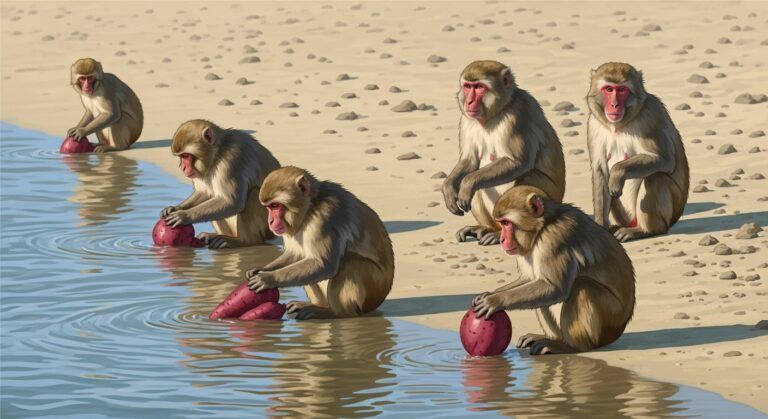

In the mid-2020s, some researchers argued that plate tectonics and the right balance of oceans and continents may be more critical than people assumed. On Earth, plate tectonics helps regulate carbon over long timescales and recycles nutrients. If tectonics is rare, complex life could be rarer than simple life.

This line of thinking doesn’t require any dramatic assumptions. It just says that “Earth-like” might be a narrower target than “rocky planet in the habitable zone.”

Scientists still debate which factors are genuinely required, and which are just how Earth happened to work. Candidates often discussed in the literature include:

- long-lived liquid water

- a stable climate over billions of years

- active geology (possibly plate tectonics)

- a protective magnetic field (still debated as a necessity)

- manageable impact history (not too quiet, not too catastrophic)

The honest conclusion here is modest: planets may be common, but the full recipe for complex life might be less familiar.

Short-lived civilizations: technology may not last long enough to overlap

Even if intelligence arises, another bottleneck could be time.

Two civilizations could exist in the same galaxy but miss each other by a million years, like two ships crossing the ocean in different centuries. In that case, the galaxy might not look busy at any given moment.

A “short-lived civilization” explanation can include different endings, and none are proven:

- self-destruction (war, runaway climate damage, engineered pathogens)

- gradual collapse or loss of technological capacity

- a shift toward quiet communication methods

- a choice to stop broadcasting because it’s wasteful or risky

This idea is uncomfortable because it touches our own risks, but it doesn’t need science fiction. It only needs one assumption: the window for detectable technology can be short.

They might be quiet, hidden, or using tech we cannot spot yet

Some explanations don’t rely on rarity. They rely on detection limits and behavior.

Deliberate quietness. A civilization might avoid broadcasting because it sees unknown contact as risky. We can’t test motives directly, but we can look for signs that don’t depend on friendly outreach.

The “zoo” style idea. Some versions claim that advanced civilizations choose not to interact with emerging ones. This is hard to test because it’s about intent, not physics. Still, it reminds us that “no contact” does not automatically mean “no one out there.”

Different technology paths. Aliens may communicate with tight, directional beams that rarely sweep Earth. They may compress or encrypt signals so they look like noise. Or they might build systems that produce signatures we haven’t prioritized, such as unusual atmospheric chemicals or waste-heat patterns.

A related recent idea sometimes described as “radical mundanity” suggests that some civilizations could be only slightly ahead of us, not millions of years ahead. If so, their signals could be weak, local, and easy to miss. That’s speculative, but it fits within known limits of detection.

What could actually move the Fermi Paradox from debate to data

The best way forward is to focus on things we can measure. Three areas stand out: exoplanet surveys, atmospheric studies, and broader technosignature searches.

We are already in a better place than Fermi was. Exoplanet science has shown that planets are common, and Kepler-era results suggest small, rocky planets are not rare. The next step is harder: learning what those worlds are like.

Exoplanet atmospheres: looking for possible biosignatures, carefully

Scientists study some exoplanet atmospheres by watching starlight pass through a planet’s air during a transit. Molecules absorb specific wavelengths, leaving faint fingerprints.

Possible biosignatures often discussed include combinations of gases that are hard to maintain without a steady source, such as oxygen with methane. Even then, false positives are a real risk. Geology and sunlight can mimic life-like signals in some cases.

A good example of why restraint matters is K2-18b, a planet about 120 light-years away: early JWST-based discussions raised public interest in possible life-related gases. Follow-up analysis in 2025 did not confirm a strong biosignature case. The more careful takeaway is that K2-18b remains interesting, but it’s not evidence of life.

For atmospheric claims to become persuasive, researchers look for:

- higher-quality spectra with better signal-to-noise

- Repeated observations that agree

- models that rule out non-biological sources as best as possible

- multiple lines of evidence that fit together

Even then, “life” can remain a hypothesis until the evidence becomes hard to explain any other way.

Technosignatures: beyond radio, what “alien technology” might look like

Technosignatures are measurable signs of technology. Radio is still part of the picture, but it’s no longer the only idea.

Examples that researchers discuss because they can be tested include:

- repeating narrowband radio signals that track a star’s position

- laser pulses that appear artificial due to timing and spectral traits

- unusual waste heat (infrared excess) consistent with large-scale energy use (still hard to separate from dust and natural sources)

- industrial chemicals in an atmosphere that are hard to explain naturally, depending on context and abundance

None of these is easy. The value is that they convert a vague question into a specific search: “If a civilization did X, what would our instruments see?”

Over time, more exhaustive surveys, better instrumentation, and open data practices can also reduce the odds that a real signal gets dismissed or missed.

If you enjoyed this, also read- Real Unexplained Phenomena That Still Puzzle Scientists

Final Thoughts

The Fermi Paradox exists because expectations are high and confirmed evidence remains missing. The most straightforward explanations remain on the table: life could be rare, technological windows could be short, or signals could be complex to detect with the searches we’ve done.

What changes in this story won’t make it a better argument. It will be better measurements, from exoplanet atmospheres to more exhaustive technosignature surveys, and careful follow-up when something looks odd. Until then, Fermi’s question stays alive for a good reason: it’s one of the few big scientific puzzles that can still surprise us without breaking any known laws of nature.

Fermi Paradox FAQ

Straight answers on what the paradox is, what we’ve actually searched, and why the galaxy can still look quiet.

What is the Fermi Paradox?

The Fermi Paradox is the gap between what we might expect in a huge, old, planet-filled galaxy and what we actually observe: no confirmed alien signals, probes, or other repeatable signs of a technological civilization beyond Earth.

Did Enrico Fermi really say “Where is everybody?”

That phrase is the popular summary of his point: if intelligent life is common and spreads, why don’t we see evidence? The exact wording varies in retellings, but the core question is the same.

Is the Fermi Paradox proof that aliens don’t exist?

No. It’s a question about missing evidence and incomplete searches. The paradox highlights uncertainty in our assumptions about how often life appears, how long civilizations last, and how detectable they would be.

What have we actually searched so far?

Most SETI work has focused on listening for radio signals since the 1960s, with additional efforts looking for optical or near-infrared laser-like pulses. We’ve sampled only a small slice of the sky, frequencies, and time windows that could carry a signal.

Why might the galaxy look quiet even if life is common?

Signals fade with distance, civilizations may be “radio loud” for only a short period, we don’t monitor targets continuously, and advanced communication could be narrow-beam, encrypted, or otherwise hard to spot with current surveys.

What is a technosignature?

A technosignature is a measurable sign of technology, such as a repeating narrowband radio signal, an artificial-looking laser pulse, unusual infrared waste heat, or atmospheric chemicals that are difficult to explain naturally in context.

What is the Great Filter?

The Great Filter is the idea that one step on the path from chemistry to long-lived technological civilization is extremely unlikely. The “filter” could be behind us (we got lucky) or ahead of us (civilizations often fail after reaching high capability).

What could turn the Fermi Paradox from debate into data?

Better measurements: broader technosignature surveys, stronger follow-up on candidate signals, and more detailed exoplanet atmosphere observations that can test biosignature and false-positive scenarios with repeatable data.