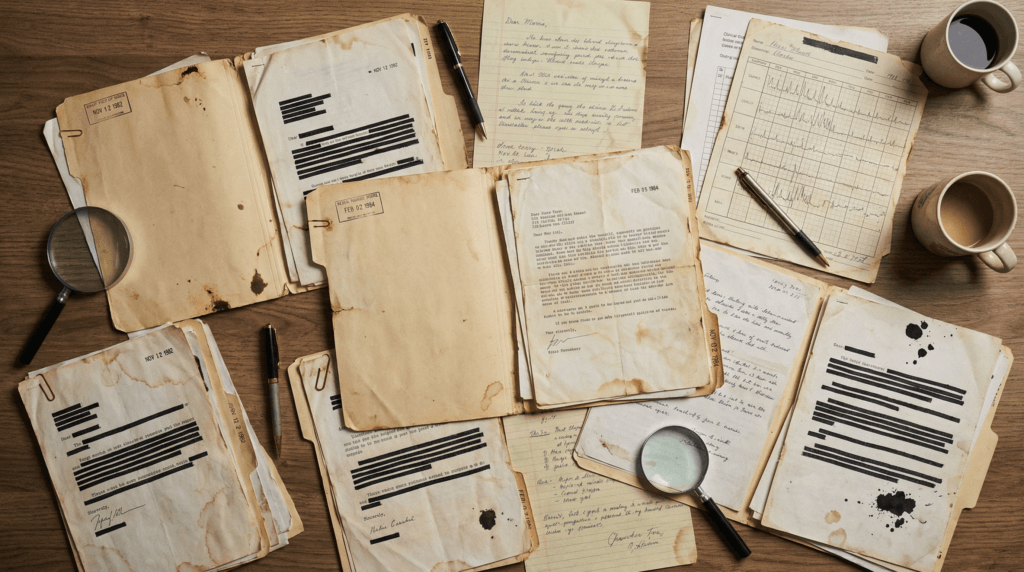

Most famous UFO stories run on retellings. The Cash Landrum case is different because it left a thick paper trail: medical visits, investigator files, and a federal lawsuit that forced agencies to answer questions on the record.

That doesn’t mean the core mystery is solved. It means we can separate what’s documented from what’s remembered, and what’s asserted from what can be verified.

Below is a careful look at the reported encounter, the health claims, the available documents, and the hard limits investigators still encounter as of January 2026.

What the witnesses reported seeing (and what can be checked)

On December 29, 1980, Betty Cash was driving near Huffman, Texas, with Vickie Landrum and Landrum’s young grandson, Colby. Their shared account, repeated in interviews and case files, describes a bright object above the road, often described as diamond-shaped, emitting flame or intense light. They reported strong heat inside the car and rapid-onset physical discomfort.

The most specific part of the story is also the most contested: the witnesses said they saw a large formation of military-style helicopters, commonly described as CH-47 Chinooks, around or near the object. Counts vary by retelling, but the usual claim is “around 20” or more. A key point for readers who like clear evidence is this: the helicopter count is based on witness testimony, not a number derived from publicly available flight logs.

What can be checked with more confidence is the setting and timing. The location is known, the date is fixed, and the witnesses’ identities are not anonymous. Investigators can also confirm that the case drew serious attention in UFO research circles and later in court filings. Basic summaries that track those broad facts (without proving the cause) appear in reference works such as the folklore encyclopedia entry on the Cash Landrum encounter.

There’s also a quieter but important “confirmable” element: after the event, the witnesses did not simply tell a story and move on. They sought medical care, and they pursued legal action. That created timestamps, names, and documents that investigators can still review.

The medical claims: symptoms are real, the cause is the problem

The medical side is why the Cash Landrum case has stayed alive. All three witnesses reported becoming ill soon after the encounter, with Cash described as the most severely affected. Symptoms commonly listed across case summaries include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, eye irritation, skin redness or blistering, headaches, and hair loss.

Two things can be true at once:

- People can be genuinely sick, and their suffering can be documented by clinicians.

- The jump from “sick after an event” to “injured by radiation from a craft” is a much higher bar.

Acute radiation syndrome has a known clinical pattern, but in real life, it’s often hard to diagnose without dosimetry, lab trends, and a clear exposure source. Many conditions can mimic parts of it, including chemical exposures, heat injury, infections, medication reactions, and intense stress with dehydration. Hair loss, for example, can follow radiation exposure, but it can also follow severe illness and other triggers.

What do investigators actually have in hand? Not a peer-reviewed case report that conclusively measures radiation dose from this event. What they do have (based on publicly circulated files and correspondence) are doctor visits, statements by physicians, and later letters and summaries. A useful collection point for the medical-document debate is the archive-style work gathered by researchers who tracked correspondence and claims over time, including G. P. Posner’s documentation page on the case’s medical questions. Even there, the emphasis is often on what was claimed and how it was supported in letters, rather than on an independent medical confirmation of the exposure source.

A careful way to say it is this: the reported symptoms are part of the record, but the mechanism that caused them is not settled by the surviving documentation.

The paper trail: why this case is unusually traceable

A lot of UFO cases are “soft” in the sense that they rely on memory and media. The Cash Landrum case became “harder” because it generated paperwork across several systems:

Investigator files. Researchers affiliated with civilian UFO groups interviewed witnesses, gathered statements, and preserved timelines. This material varies in quality, but it at least shows how the story developed and when key details were recorded.

Medical records and correspondence. Portions of the medical narrative exist as summaries, letters, and recollections by involved parties. Not all clinical files are publicly available, and privacy restrictions limit what can be independently verified today.

The lawsuit. The witnesses sued the U.S. government, seeking damages and arguing that some government-linked craft or operation caused their injuries. That forced responses from agencies and put the claim into a formal setting where assertions could be challenged.

For readers who care about primary-source hunting, one of the most practical starting points is a curated index of reports, letters, and articles such as the Cash Landrum document collection. Collections like this don’t “prove” anything by themselves, but they help you see what exists, what’s missing, and how the record was built.

The lawsuit ended without the outcome the plaintiffs wanted. A central reason, repeated in summaries of the case history, is that the court found insufficient evidence linking the incident to U.S. government responsibility. That legal result often gets misread as “the event didn’t happen.” Courts usually decide narrower questions: what can be shown, under rules of evidence, to meet legal standards of liability.

What investigators can and can’t confirm (a reality check)

By 2026, the case remains in a stable state: heavily discussed, heavily filed, and still unproven in its most dramatic parts. Here’s the cleanest split between what can be supported and what can’t.

| Question people ask | What investigators can confirm | What they can’t confirm |

|---|---|---|

| Did the witnesses report a close encounter and later illness? | Yes, through repeated statements and medical visits described in case files | The exact trigger for each symptom |

| Were helicopters present that night? | That helicopters were reported, and some secondary witnesses have been mentioned in case literature | A verified unit, flight logs, mission orders, or a released after-action record |

| Was it “radiation exposure”? | Some involved doctors and investigators discussed radiation as a possibility in their writings | A measured dose, a validated exposure source, or a peer-reviewed clinical confirmation tied to the object |

| Was it a government operation? | Those agencies denied involvement in testimony and responses during the legal process | A declassified program admission that matches the scenario |

Skeptical reviews tend to focus on the same weak point: independent corroboration. If a large group of military helicopters escorted something over a public road, the hope is that a matching paper trail would exist, even decades later. The strongest skeptical arguments often live in the gap between “extraordinary logistical claim” and “no matching operational record surfaced.” One widely circulated skeptical examination is Robert Sheaffer’s piece in Skeptical Inquirer, which argues that the classic narrative frays when external confirmation is demanded.

At the same time, believers sometimes overstate what the case proves. A grim medical aftermath doesn’t automatically authenticate a UFO explanation. It only tells us that something bad happened to these people, and the timeline matters.

If you want a broader frame for how UFO claims fit (or don’t fit) into the bigger question of extraterrestrial contact, it helps to keep separate bins for evidence types. A sighting case, even a famous one, isn’t the same category as repeatable scientific detection. That distinction is central to Understanding the Fermi Paradox and Its Implications, where “quiet skies” and “anecdotes” are treated as distinct kinds of input.

Conclusion: a case with documents, and still no closure

The Cash Landrum case survives because it’s partly traceable. There are names, dates, interviews, medical claims, and a lawsuit that pushed the story into official channels. That’s more than most cases ever get.

But the central questions remain open. No released records tie the helicopters to a unit, and no independent medical evidence links the illnesses to a proven radiation source from the reported object. If new documents ever surface, they’ll matter because this case is built on paperwork as much as memory.

If you’re reading the file today, the best habit is simple: treat the suffering as real, treat the claims as claims, and keep asking what can be checked.

Key Takeaway / Summary

The Cash Landrum UFO case is anchored by real documents, medical claims, and a formal lawsuit. While investigators can confirm the timeline and aftermath, the cause of the reported injuries and the nature of the encounter remain unverified.