Ball lightning sits in a strange middle ground, part long-running eyewitness lore, part unfinished physics. The usual description is consistent enough to catch your attention: a bright, floating sphere that appears during thunderstorms, moves in ways people don’t expect, lasts longer than a normal lightning flash, and then disappears.

Here’s the catch. Ball lightning is often reported but captured clearly only on rare occasions. That leaves researchers with a thin file: human recollection, scattered damage notes, and a small set of instrumented observations. It’s workable, but it’s not the kind of evidence base that makes clean, final answers easy.

What follows is the careful version, the points that stronger reports tend to share, the lab effects that can be reproduced (and what still can’t), plus why ball lightning keeps resisting a tidy explanation.

What Counts as “Ball Lightning” (and What Doesn’t)

In scientific papers, ball lightning is usually treated as a category of reports rather than a single confirmed, well-measured object. A solid place to start is a historical review that tracks how observers and researchers have described it over time, including which features repeat and which contradict each other (see History of Geo- and Space Sciences: a brief history of ball lightning observations).

Across many accounts, commonly reported traits include:

- A glowing ball (often described as around tennis ball to grapefruit size, with wide variation)

- A lifetime measured in seconds (sometimes shorter, sometimes longer)

- Motion that doesn’t look like a simple ember falling or a flame rising

- A link to thunderstorms, with some reports describing indoor appearances

- A sudden end, either quiet or accompanied by a loud noise

It also matters what can imitate ball lightning. St. Elmo’s fire (Not the Film!) can create a steady glow on pointed objects. Power lines can arc. Bright lightning can leave afterimages that feel like a moving light. Reflections in glass can also look like “a light inside the room” during a storm. A serious claim has to be weighed against these simpler possibilities first.

The Best Real World Reports: Patterns that Keep Showing Up

A useful ball lightning report usually has two things going for it. First, a witness who can clearly describe the setting. Second, details that can be checked later, such as storm timing, power outages, broken glass, scorch marks, or other localized damage.

The 2021 HGSS review is helpful because it doesn’t treat every story the same. It pulls together many reports, including those from scientists and trained professionals, and shows how careful observers tried to record what they could, even when they weren’t sure what they were seeing.

Some recurring themes in higher-quality reports are stated conservatively:

Indoor Appearances are Reported, But They’re Hard to Confirm

People often say the glowing ball came through a window, down a chimney, or appeared near a wall. Those details matter because they press against the easiest explanations.

They also raise a basic question. If the object is a hot plasma, why doesn’t it scorch everything nearby right away? Some accounts mention heat, burns, or a sharp odor (often described as sulfur or ozone). Many others don’t. That mix is one reason researchers stay cautious about treating any single report as definitive.

The Motion Descriptions are Often Specific

Witnesses don’t only say “there was a light.” They describe drifting, pausing, steady travel, movement that seems to ignore airflow, or a straight-line path at a fixed speed. Specificity doesn’t guarantee accuracy, but it’s one reason the topic doesn’t fade away.

“It Exploded” Shows Up A Lot, But Hard Evidence Shows Up Less

A loud bang at the end appears in many accounts. Physical traces are less common, and when they exist, they’re not always documented in a way that clearly separates them from ordinary lightning damage.

Instrumented Evidence, and Why It’s Still Limited

People want the obvious things: a clear video, a spectrum, a sensor readout, and a clean set of measurements. That’s fair. The problem is timing. Ball lightning reports describe something brief and unpredictable, so the odds of having the right calibrated instrument aimed at the right place at the right second are low.

Because natural data are scarce, some researchers compare lab plasma balls and discharge effects to reported properties. One example, indexed in NASA ADS, frames its results as a comparison point rather than a final solution: “Generation of confined plasma balls propagating along discharge channels.”

Even when a camera captures something round during a storm, researchers still have to ask basic questions:

- Is it blown-out sensor glare or lens flare?

- Is it a spark close to the camera rather than an object at a distance?

- Could it be a burning particle from a strike point?

- Is there any calibrated reference for size and distance?

If those questions can’t be answered, the footage may be interesting, but it won’t support a reliable physical model.

Lab Work and “Ball Lightning Analogs”: What Can Be Recreated

Laboratory studies tend to chase one of two goals. Either create a free-floating luminous object in the air, or reproduce one or two key traits (brightness, lifetime, motion) using known physics.

An example of an engineering-focused setup designed to generate and measure laboratory analogs under controlled conditions is the Installation for Studying the Laboratory Analog of Ball Lightning. Work like this matters because it turns a story problem into a measurement problem. Researchers can vary the voltage, electrode shape, humidity, and materials, then record the resulting changes.

A key caution stays on the table. A lab “fireball” can be real plasma and still not match natural ball lightning. It might remain tied to a discharge channel, be fed by currents the experiment provides, or depend on vaporized material that doesn’t reflect open-air conditions.

The “Soil and Silicon” Experiments

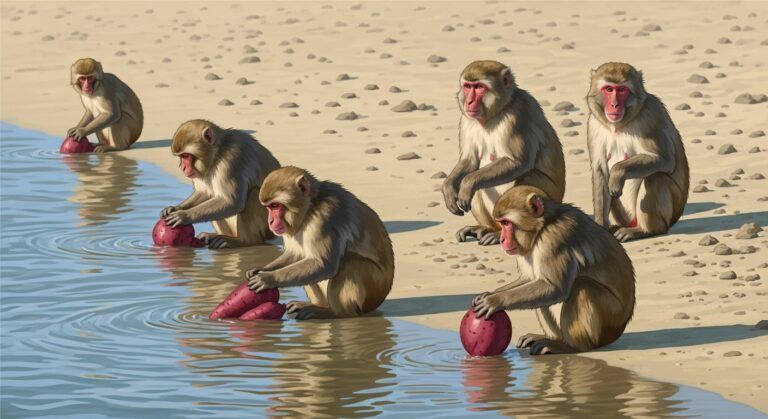

One of the best-known grounded ideas links ball lightning to lightning strikes on soil. The proposal is straightforward: a strike can vaporize silicon-rich material, and as that vapor cools, it may form glowing particles or aerosols that oxidize and emit light. Physics World summarized this approach in an accessible way, tying it to published work: “Burning soil fuels ball lightning.“

This class of models has a clear strength: it connects the glow to real chemistry and real materials at a strike site. It also has limits. It doesn’t automatically explain reports of luminous objects forming away from the ground, persisting indoors without obvious burn damage, or moving in the directed ways some witnesses describe.

Microwave and Other Theories, Interesting, Not Confirmed

Some theories suggest that lightning could generate microwaves that help trap energy in a plasma structure. Others propose different ways energy might be stored and released. A widely cited example is a theoretical paper in Scientific Reports titled “Relativistic-microwave theory of ball lightning.“

The status matters here. These are attempts to match reported traits, not proof that nature uses that mechanism in real storms.

Why Ball Lightning Is So Hard To Study, Even If It’s Real

Ball lightning breaks several conditions that make atmospheric science easier.

It Doesn’t Show Up on Demand

Most field research depends on repeatable observation. Ball lightning doesn’t cooperate. Even people who spend a lot of time near storms rarely report it.

The Definition Problem Doesn’t Go Away

Several phenomena can look similar in a fast, stressful moment. More stories don’t always sharpen the picture. Researchers need a working definition strict enough to filter false positives, but broad enough not to discard the rare, better-documented cases.

Witness Memory is Useful and Limited

Many reports come from people who had only seconds to watch something bright and unusual while thunder and lightning were already in play. Human perception under stress isn’t a precision instrument. That doesn’t mean the witness is lying. It means testimony has limits.

The Best Chances to Observe It Are Also Risky

If something appears near a strike point, the environment is already dangerous. Setting up sensors near high-voltage events can be done, but it’s not casual work.

Labs Can Match the Look Without Matching the Cause

A lab can produce a glowing sphere. That’s progress. But “similar appearance” and “same mechanism” are not the same claim, and that gap is where the ball lightning puzzle often stalls.

Conclusion: Consistent Reports, Incomplete Data

Ball lightning stays in the scientific conversation for a simple reason. Many reports share overlapping details, enough to avoid dismissal, but the evidence is still too uneven to treat the phenomenon as settled.

The most defensible path has been careful and slow: build better catalogs of higher-quality sightings, keep pushing laboratory analogs toward better measurement and clearer limits, and be honest about where the data stop and theory begins.

If you ever see a convincing case, the most useful response isn’t a dramatic retelling. It’s calm documentation: time, location, storm conditions, distance cues, and any safe video that includes stable reference points. For now, ball lightning remains a rare event with more questions than clean measurements, and that’s the most accurate place to leave it.

If you enjoyed this post, then read more in Real Unexplained Phenomena That Still Puzzle Scientists

Ball Lightning FAQ

Quick answers pulled from the article: real reports, lab analogs, and why the mystery survives.

What do scientists mean by “ball lightning”?

It’s treated as a category of recurring reports rather than a single, fully measured phenomenon. The overlap between accounts matters, but the data remain uneven.

What are the most common traits people report?

A glowing sphere during a thunderstorm, lasting seconds, moving in unexpected ways, and ending abruptly—sometimes quietly, sometimes with a loud bang.

Why are clear photos and measurements so rare?

The event is brief, unpredictable, and often happens in dangerous conditions. Even video needs distance cues and calibration to be useful.

What can be mistaken for ball lightning?

St. Elmo’s fire, power-line arcing, reflections, afterimages, and camera artifacts can all mimic a floating light.

Can labs recreate ball lightning?

Labs can create glowing plasma-like spheres, but many depend on controlled energy inputs that may not reflect natural storm conditions.

What is the “soil and silicon” idea?

Lightning may vaporize silicon-rich soil, producing glowing particles as they oxidize. It explains some sightings, but not all reported behaviors.

What about microwave-based theories?

Some models suggest trapped electromagnetic energy could sustain a glowing structure, but real-world confirmation remains limited.

If I see something like this, what should I document?

Note the time, location, storm conditions, and distance cues. If filming safely, include stable reference points to judge size and motion.