Ball Lightning: What the Best Reports Agree On, and Why That Matters

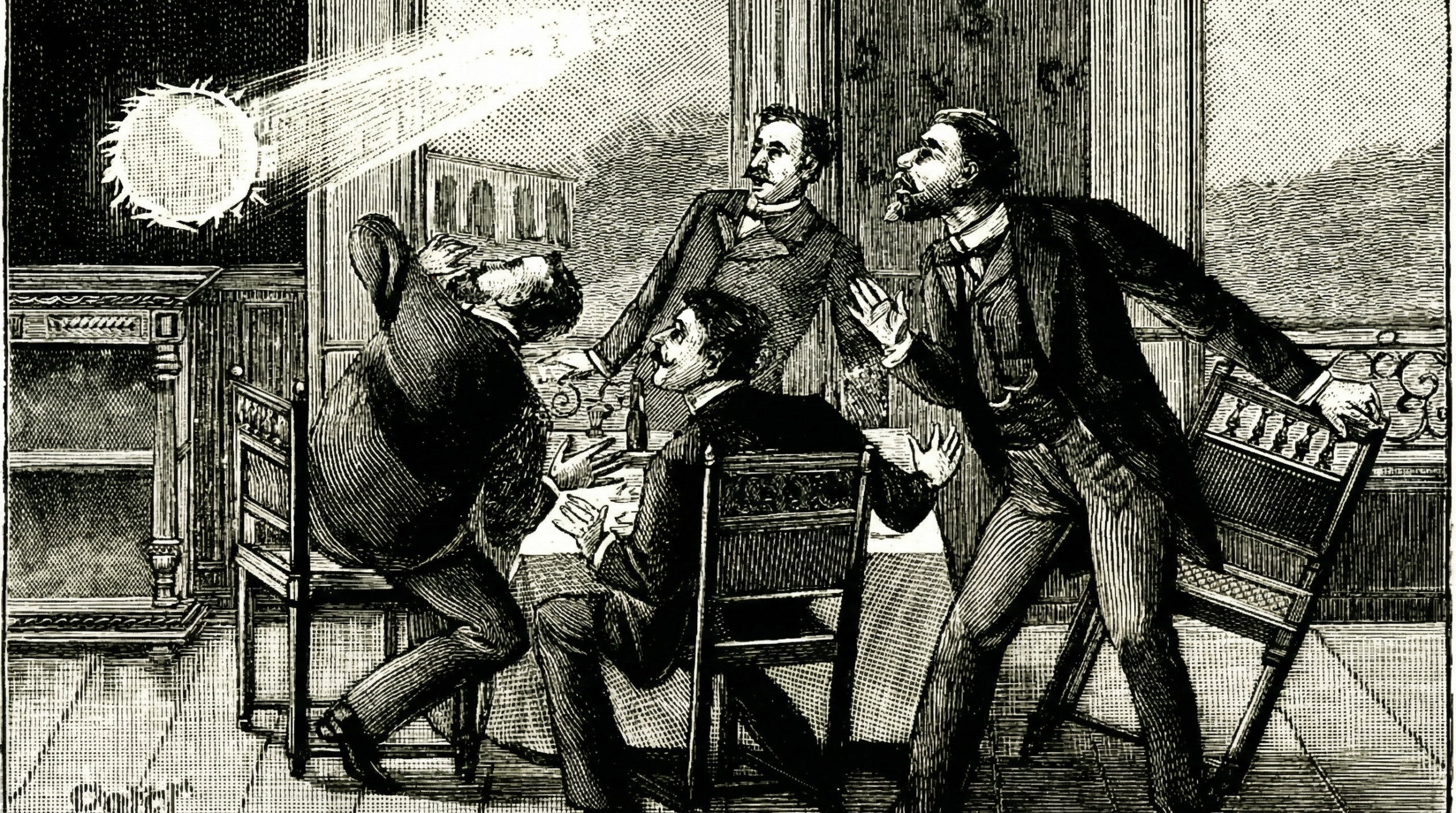

Ball lightning lives in an uncomfortable space. Too strange to ignore. Too slippery to pin down. People describe a bright, floating sphere that appears during storms, moves with intent, lasts longer than a lightning flash, and then vanishes—sometimes quietly, sometimes not. The reports come from farmers and pilots, engineers and meteorologists, people with nothing to gain by embellishing. And yet the recordings are scarce. The instruments are late. The explanations never quite close the gap.

What follows isn’t a grab-bag of theories. It’s a sorting exercise. When you strip away the noise and focus only on the strongest, most consistent accounts, a pattern emerges. Not a single answer, but a set of agreements that matter.

What counts as “ball lightning” (and what doesn’t)

In careful writing, ball lightning isn’t treated as a confirmed object so much as a class of reports. That distinction matters. The label usually applies when several features line up at once, not just one.

First, duration. These events last seconds, sometimes longer. That alone separates them from ordinary lightning, which is over almost as soon as it’s seen.

Second, form. Witnesses describe spheres or near-spheres, typically the size of a grapefruit to a basketball. The edges glow. The light is steady, not flickering like a flame.

Third, motion. This is where many explanations stumble. The objects drift. They move horizontally. They pause. Some appear to track along walls or wires. A few reports describe them changing direction abruptly, without obvious aerodynamic cues.

Fourth, context. Most sightings occur during or just after thunderstorms. That connection is strong, even when the event happens indoors.

Finally, interaction. Ball lightning has been reported passing through windows, traveling down chimneys, or moving through aircraft cabins without shattering glass. In rare cases, it leaves scorch marks, melted metal, or a sulfur-like smell.

If a story only includes one of these elements—say, a brief flash or a vague glow—it’s usually excluded by serious catalogs. That filtering alone removes many weak claims.

Who reports it, and why that matters

One reason ball lightning refuses to go away is the profile of many witnesses. These aren’t all late-night stories told decades later. Pilots have reported luminous spheres inside cockpits. Engineers have described slow-moving lights in industrial settings. Weather observers have documented events with timestamps and conditions.

Some of the most cited modern reports were investigated by teams associated with places like Los Alamos National Laboratory and the University of New Mexico, not because the phenomenon fit a neat theory, but because the descriptions were too consistent to dismiss outright.

This doesn’t make every account correct. Human perception is fallible, especially under stress. But when people trained to notice details independently describe similar behavior, the burden of explanation shifts. You can’t wave it away as mass fantasy without doing more work.

The few points most strong reports agree on

When researchers compile only the best-documented cases, a handful of agreements keep surfacing.

The light source appears self-contained. Witnesses often note that it doesn’t illuminate the surrounding area the way a flame or arc would. It glows, but selectively.

The motion is slow relative to lightning, measured in feet per second, not miles per hour. That suggests something other than a simple discharge.

The objects are quiet while present. The sound, if any, tends to come at the end—an abrupt pop, bang, or hiss as the phenomenon disappears.

And crucially, the energy budget is ambiguous. Some events cause damage inconsistent with a low-energy glow. Others fade without leaving a trace. That spread is hard to reconcile with a single mechanism.

These aren’t dramatic claims. They’re mundane ones. And that’s why they’re helpful.

Why lab experiments keep coming up short

Laboratories have not been idle. Researchers have created glowing plasma balls using microwaves, electrical arcs, and vaporized materials. Some experiments produce floating, luminous structures that look convincing on video.

The problem is persistence and context.

Many lab creations last fractions of a second. Others require continuous energy input. Some only exist in controlled atmospheres. They mimic appearance, but not behavior. Or behavior, but not lifespan.

There’s also the scale problem. A phenomenon that occurs naturally during storms may rely on conditions that are hard to reproduce indoors—complex electric fields, rapid pressure changes, and specific materials present in the environment.

So when a paper claims success, it’s usually partial. It explains one slice of the reports, not the whole set. That doesn’t mean the work is wrong. It means it’s incomplete.

The classification problem no one likes to admit

Here’s where judgment matters.

Most popular explanations quietly assume that ball lightning is a single phenomenon with a single cause. Plasma, for example. Or burning silicon vaporized from soil. Or microwave-trapped energy.

But the evidence resists that framing.

Some reports involve high energy and damage. Others don’t. Some involve outdoor motion in the open air. Others happen inside sealed spaces. Some end explosively. Others fade.

If you stop forcing them into a single box, a different picture emerges. “Ball lightning” may be a name we give to several rare electrical phenomena that share surface features but not underlying physics.

That’s uncomfortable. It means there may never be a single, elegant explanation. Instead, there could be a small family of mechanisms triggered under similar storm conditions, each producing something that looks roughly spherical and luminous to a human observer.

From a distance, they blur together. Up close, they diverge.

The hardest cases to explain

A few categories remain especially stubborn.

Indoor appearances top the list. Passing through glass without damage challenges straightforward plasma models. Some researchers suggest microfractures, electromagnetic coupling, or misperception. None fully satisfies all reports.

Controlled motion is another problem. Objects that appear to hover or follow a path without visible forces push the limits of simple electrical explanations.

And then there’s the timing. Ball lightning sometimes appears after the main lightning strike has ended. That delay complicates models that rely on immediate discharge effects.

These cases don’t prove anything exotic. But they mark the edges where current models thin out.

Why this still matters

It’s tempting to treat ball lightning as a curiosity, a footnote for trivia nights and mystery shows. But that misses the point.

This phenomenon sits at the boundary of observation and theory. It exposes how science handles rare events that can’t be summoned on demand. Progress comes slowly, through pattern recognition, not decisive experiments.

Ball lightning also serves as a caution. When explanations pile up without judgment, they create the illusion of understanding. Sorting, weighing, and discarding is harder work—but it’s the only way forward.

There is something real here. Not a single thing, perhaps. But a cluster of related events that thunderstorms occasionally produce. The honest answer isn’t “mystery solved” or “nothing to see.” It’s that the best reports agree on enough to take seriously, and disagree enough to resist tidy closure.

That tension isn’t a failure of science. It’s how science looks when it’s still thinking.

Ball Lightning FAQ

What is ball lightning?

Ball lightning is the name given to rare storm-related reports of a glowing, usually spherical object that can last longer than a normal lightning flash and move in unusual ways before fading or ending abruptly.

Is ball lightning real or just misidentified lightning?

It’s treated as a real observation problem, not a settled fact. Some reports are likely misidentifications, but the most consistent accounts are detailed enough that researchers continue to study it as a genuine atmospheric electricity mystery.

How long does ball lightning last?

Reports commonly describe seconds rather than a split-second flash. Some accounts go longer, but the “seconds-long” duration is one of the traits that makes it stand out.

How big is ball lightning?

Witness descriptions vary, but it’s often compared to everyday sizes like a grapefruit or basketball. Size estimates aren’t always reliable in storms, so researchers look for repeated patterns across many reports.

Can ball lightning go through windows or appear indoors?

Some of the hardest-to-explain reports involve indoor appearances or movement near windows, chimneys, wiring, or metal objects. These accounts are part of why a single simple explanation keeps falling short.

Is ball lightning dangerous?

It can be. Many reports end harmlessly, but others describe burns, damaged wiring, scorched surfaces, or a loud explosive ending. The risk is treated as unpredictable, which is not comforting, but it’s honest.

Has ball lightning ever been recorded on video?

There have been a few recordings and instrumented observations, but they’re uncommon. The phenomenon is rare, unpredictable, and usually over before anyone is ready to document it properly.

What causes ball lightning?

There’s no single agreed cause. Proposed models include different kinds of plasma behavior, chemical combustion of vaporized materials, and electromagnetic effects linked to storm conditions. Many researchers suspect more than one mechanism may be getting lumped under the same name.

If you enjoyed this post, then read more in Real Unexplained Phenomena That Still Puzzle Scientists