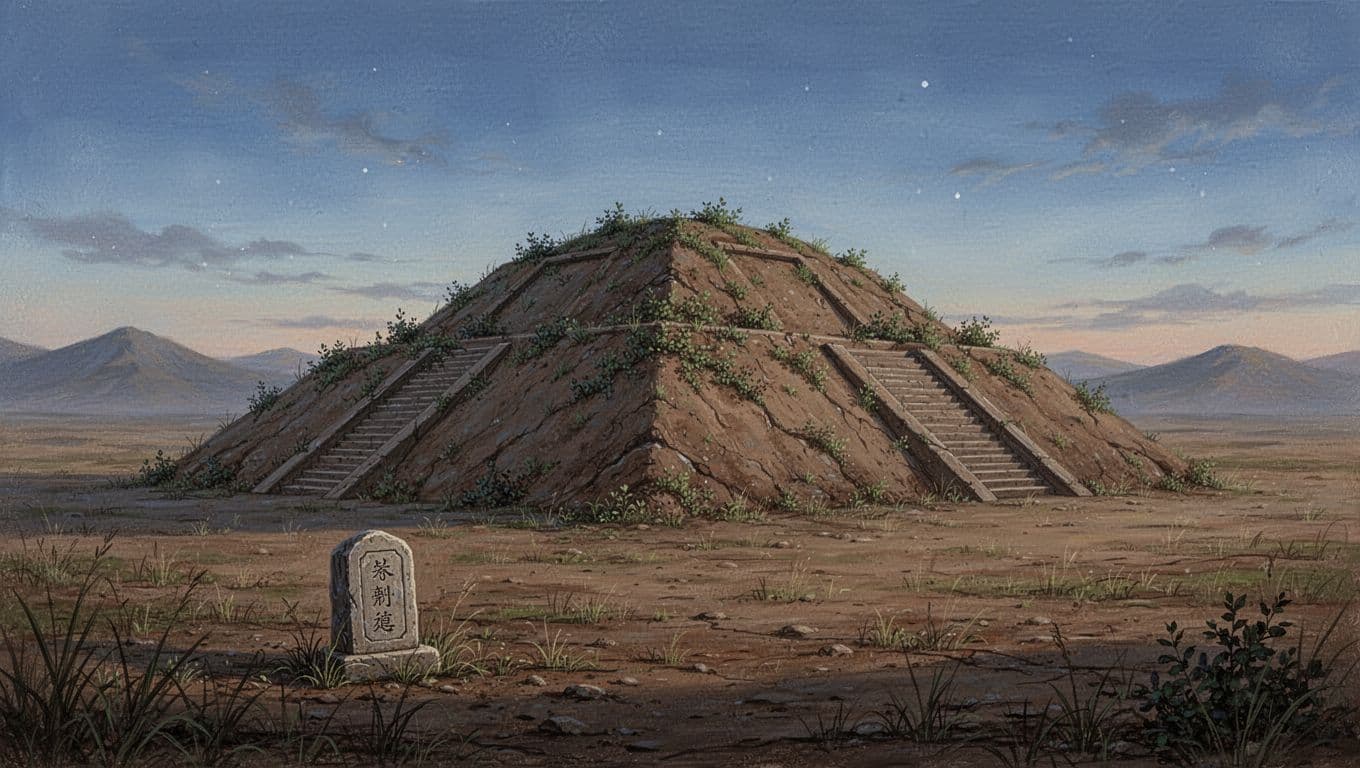

Near Xi’an, an earthen mound sits like a locked vault. It belongs to Qin Shi Huang, the man who unified China and called himself its first emperor. The site is famous, guarded, and still mostly closed to the world.

The unsettling part is what might be inside. An early historian wrote that the emperor’s tomb held “rivers” and “seas” made from mercury, set up to flow like a map of his empire. Centuries later, scientists measured mercury levels around the mound that run higher than normal.

Still, the main burial chamber remains unopened as of February 2026. That means no one can point to a pool of liquid metal and say, “There it is.” What we can do is weigh the sources, look at the measurements, and understand why officials keep the door shut.

What the oldest records really say about “mercury rivers” in the tomb

The mercury claim doesn’t come from rumor mills or modern thrill writing. It comes from Sima Qian, a court historian of the Han dynasty who wrote the Records of the Grand Historian about a century after Qin Shi Huang died in 210 BCE.

Sima Qian described a buried world built to last. He wrote of an underground palace complex, packed with valuables and crafted to mirror the emperor’s rule above ground. In that picture, mercury had a starring role. He said workers used it to model “the hundred rivers,” along with major waterways and seas, arranged to look like they flowed.

That detail stuck because it fits the whole point of the mausoleum. Qin Shi Huang didn’t just want a grave. He wanted a miniature empire that kept running after death. Mercury helped sell the illusion. It stays liquid at room temperature, it shines, and it moves. In a torch-lit chamber, it could look alive.

Sima Qian also wrote about defenses, including mechanical crossbows set as traps. He described a ceiling decorated like the sky, and a chamber stocked with treasures. Those parts matter, but the mercury line became the one people can’t shake. A liquid metal river under a sealed mound is hard to forget.

Sima Qian’s account, what he could know, and what he could not

Sima Qian wrote after the Qin fell, when people still remembered how the mausoleum machine worked. He had access to court networks, older records, and official stories that survived the dynasty change.

Even so, he didn’t open the tomb. He couldn’t walk into the central chamber and check the layout. Historians treat his account as serious evidence, because it’s early and detailed, but they also treat it as a report. It may preserve real engineering notes. It may also carry some court legend.

The key point stays simple: Sima Qian gave a clear claim, and later science found signs that match it. Yet the chamber itself remains a black box.

Why mercury would have been chosen in the first place

Mercury wasn’t a random prop. It had practical traits that suited a ruler obsessed with control.

- It stays liquid: No heating needed, so “waterways” could keep their shape.

- It reflects light: A dim chamber would turn it into a moving mirror.

- It suggests motion: Even small shifts look like a current.

- It carried ritual weight: Some early traditions linked mercury compounds to longevity practices.

There’s a darker twist. Many historians accept that Qin Shi Huang likely died from mercury poisoning tied to “immortality” medicines that used mercury. The same substance that promised eternal life may have helped kill him.

What modern science has measured at the mausoleum site (and what it still cannot prove)

Modern teams can’t drill into the main chamber and scoop a sample. What they can do is measure mercury in the soil and air around the mound, then compare it to expected background levels.

Those measurements matter because mercury can migrate. Over long spans, mercury vapor can move through cracks, porous soil, and construction seams. If a large store sits underground, small amounts can leak upward.

Researchers have reported soil readings with a peak around 1440 ppb at one spot, and an average around 205 ppb across 53 sampling points. Air testing has also reported readings up to 27 ng/m3, compared with a typical 5 to 10 ng/m3 range often cited for background conditions.

Older work, including probes used in the 1980s, fed a dramatic estimate: that the tomb complex could contain more than 100 tons of mercury. That number gets repeated a lot. It should be treated as an inference, not a measured inventory.

Meanwhile, non-invasive mapping adds another layer. Ground-penetrating radar and related surveys have outlined a large underground “palace” footprint, often described around 140 x 110 x 30 meters, with a central chamber around 80 x 50 x 15 meters. Those are model-based dimensions, but they line up with the idea of a built environment, not a single pit.

For a technical example of remote mercury detection work at the site, see the University of Lund write-up on a lidar mercury emission study.

The strongest evidence so far: mercury anomalies in soil and air

A mercury anomaly is just a reading that sits above what the local ground and air usually show. It doesn’t tell you the exact shape of the source. Still, it can flag something real.

At Qin Shi Huang’s mound, the pattern is the story. Multiple studies across different years have found elevated mercury near the burial area. That repeat signal makes pure coincidence less likely.

The best-supported statement is plain: mercury levels around the mound run unusually high. The “river map” layout inside remains unconfirmed.

Alternative explanations, and how researchers try to rule them out

There is a real complication. Some researchers point to industrial pollution in the late 1970s to 1980 as a possible contributor to local mercury readings. If outside sources raised background levels, then soil data can look more dramatic than it should.

Scientists try to sort this out by looking at where the highest readings cluster, how far they spread, and how they compare to control areas. They also compare soil results with air measurements, since vapor behavior can hint at an underground source.

Even with those checks, uncertainty stays. Without direct access, no one can prove that mercury sits in channels like rivers, or that it matches Sima Qian’s description point by point. The stronger, safer conclusion is narrower: the mound area shows elevated mercury, and that fits the ancient report.

Why the tomb stays sealed: preservation risks, worker safety, and a long game of archaeology

The refusal to open the main chamber isn’t laziness. It’s policy, and it comes from hard lessons.

First, sealed spaces preserve fragile materials. Paint, lacquer, silk, wood, and adhesives can survive for centuries when oxygen stays out. Let air rush in, and decay speeds up. Early excavation of the Terracotta Army showed how fast pigment can fade after exposure. That memory still shapes every decision.

Second, the engineering job is huge. The central chamber sits deep under the mound, often estimated around 20 to 50 meters down. Any dig needs structural support, drainage plans for groundwater, and room for conservation labs. A mistake doesn’t just ruin artifacts. It can collapse a chamber.

Mercury is not just a story detail, it is a real health hazard

Mercury can evaporate. Inhaled mercury vapor can harm the nervous system and other organs. That makes excavation a worker-safety project as much as an archaeology project.

A responsible plan would need containment, continuous monitoring, and controlled ventilation. It would also need protocols for contaminated soil and water. None of that is optional.

The lesson from earlier digs: once air gets in, damage can be fast

Sealed tombs create stable microclimates. When that balance breaks, materials can dry, crack, mold, or flake. Conservators know this pattern across many sites and time periods.

So officials play the long game. They collect data from outside. They improve non-invasive scanning. They wait for better conservation methods, because an early win can turn into permanent loss.

A Tomb Sealed by Science and Caution

The mercury rivers story survives because it rests on two solid pillars. First, Sima Qian described mercury used to model waterways inside Qin Shi Huang’s tomb. Second, modern teams measured unusually high mercury in soil and air around the mound, and remote surveys mapped a massive underground complex.

Yet the core fact doesn’t change. As of February 2026, the main burial chamber remains sealed, so no one can directly confirm the internal “mercury rivers.” That mystery isn’t just fate. It’s a choice, balancing knowledge against preservation and safety. Future proof may come from better sensing and better conservation, not from cracking the chamber open tomorrow.