Progress doesn’t move in a straight line. Sometimes an idea appears, works well enough to impress people, then slips out of view for decades. Not because it was a bad idea, but because the world around it wasn’t ready, the parts were too costly, or the problem it solved didn’t feel urgent yet.

These forgotten inventions can feel unsettling in a quiet way. They remind us that “new” often means “newly practical,” not truly new. Below are a few documented examples where the concept arrived early, proved itself in limited form, then waited for better timing.

When long-distance handwriting existed before fax machines

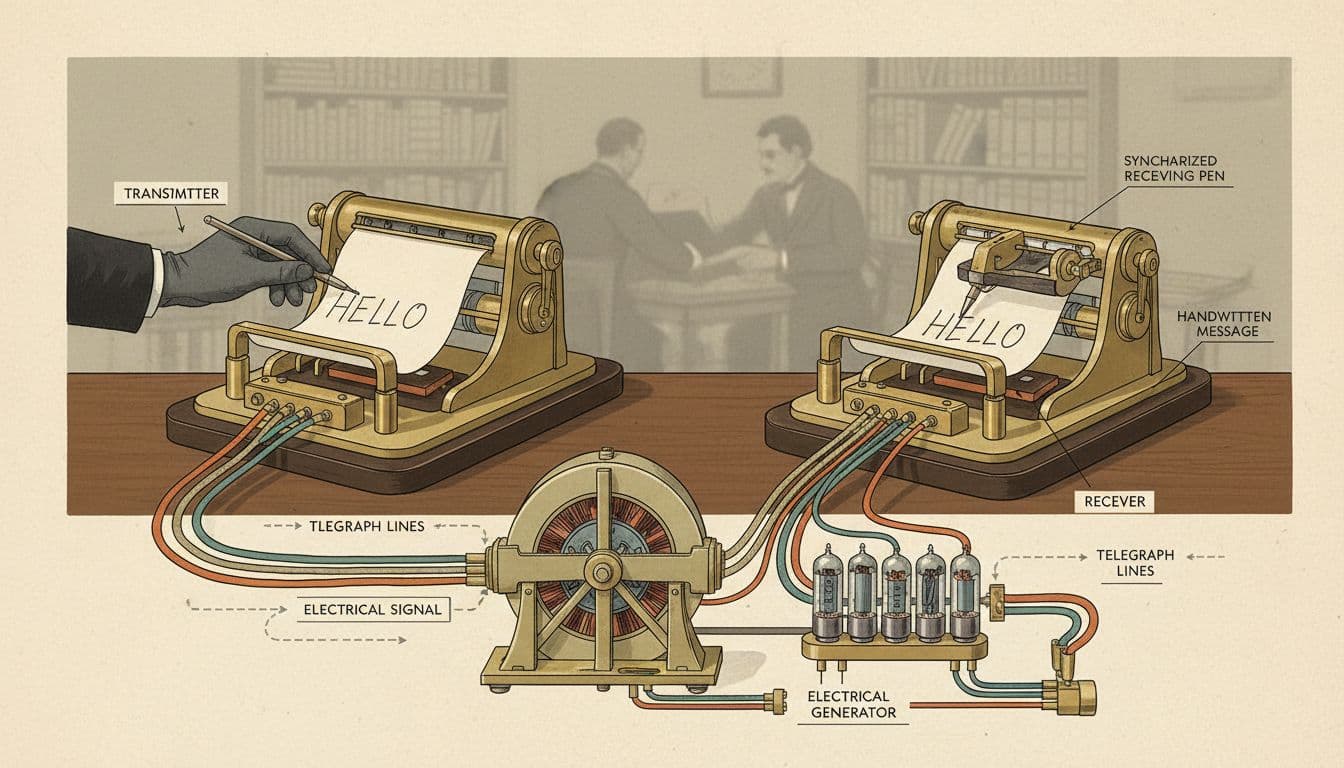

In 1888, inventor Elisha Gray patented the Telautograph, a machine designed to transmit handwriting over telegraph lines. The basic idea is easy to picture: your pen moves on one end, and a pen on the other end copies the same motion onto paper. Not a typed message, not Morse code, but your actual strokes.

It’s tempting to call it a “fax machine,” but that can mislead people. Early fax systems later relied on scanning images of documents. The Telautograph worked by mechanically tracking hand motion and re-creating it at a distance. Still, the goal was similar: send a signature, a note, or a quick sketch without a courier.

So why didn’t it become a household device? In practice, it needed infrastructure, setup, maintenance, and stable synchronization. That’s a hard sell when many offices already had workable options: letters, telegraph messages, and, soon after, telephone calls for faster back-and-forth.

Even so, the Telautograph wasn’t just a lab curiosity. It saw real-world use in certain business and public settings, enough to leave a paper trail and a place in the long arc of communication tech. If you want a quick summary of how it’s remembered today, this list-style overview includes it among other early ideas that arrived too soon: overview of the Telautograph.

The bigger lesson is simple: a device can “work,” and still fail the moment. Adoption depends on cost, reliability, and whether society has built habits that make the tool feel necessary.

The Antikythera Mechanism and the uncomfortable truth about “modern” thinking

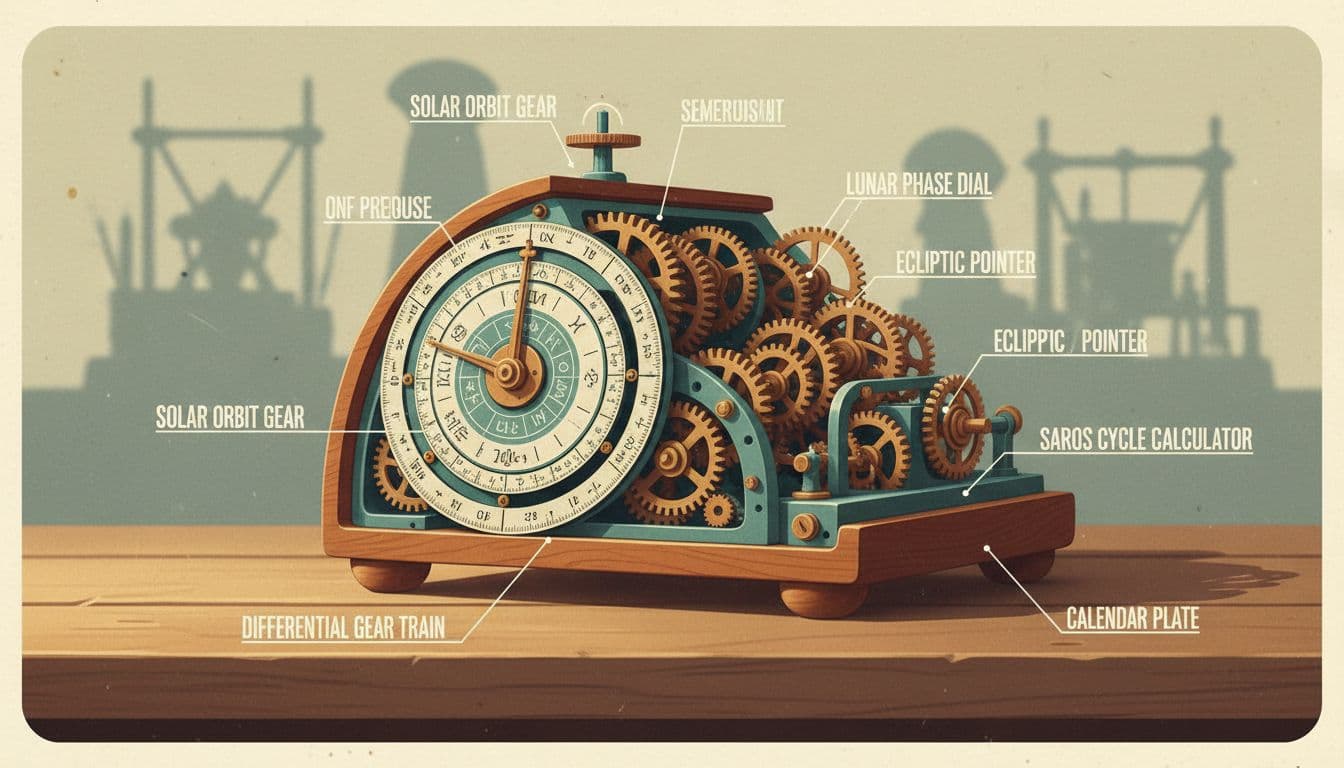

The Antikythera Mechanism is one of those artifacts that forces a reset. Discovered in 1901 in a shipwreck near the Greek island of Antikythera, it’s a corroded lump of bronze that turned out to contain complex, interlocking gears. Researchers now describe it as an ancient analog device used to model astronomical cycles.

There are limits to what can be said with certainty because the object is incomplete and badly damaged. Still, the consensus from decades of study is that it wasn’t decorative. The gearing relationships appear purposeful, and reconstructions based on surviving fragments suggest it tracked cycles related to the Sun, Moon, and calendar systems used at the time.

What makes it feel like a “forgotten invention” is not that it disappeared without any trace, but that it didn’t leave an obvious line of descendants. We don’t have a shelf of similar machines from the same era. We don’t have a clear record of a workshop that kept producing them at scale. Whatever knowledge and craft produced it, that thread either broke or stayed rare.

If you want broader context for why ancient engineering can look surprisingly advanced (and why we sometimes underestimate it), this overview collects examples under one roof: ancient inventions ahead of their time.

The Antikythera Mechanism doesn’t prove that the ancient world had modern industry. It shows something narrower and more believable: under the right conditions, skilled people can build sophisticated tools, even if society can’t support mass production or preserve the know-how for long.

Mechanical television and early electric vehicles, good ideas trapped by weak parts

A lot of forgotten inventions share the same problem: the concept is fine, but the supporting parts aren’t. Two examples show this clearly, one in media and one in transport.

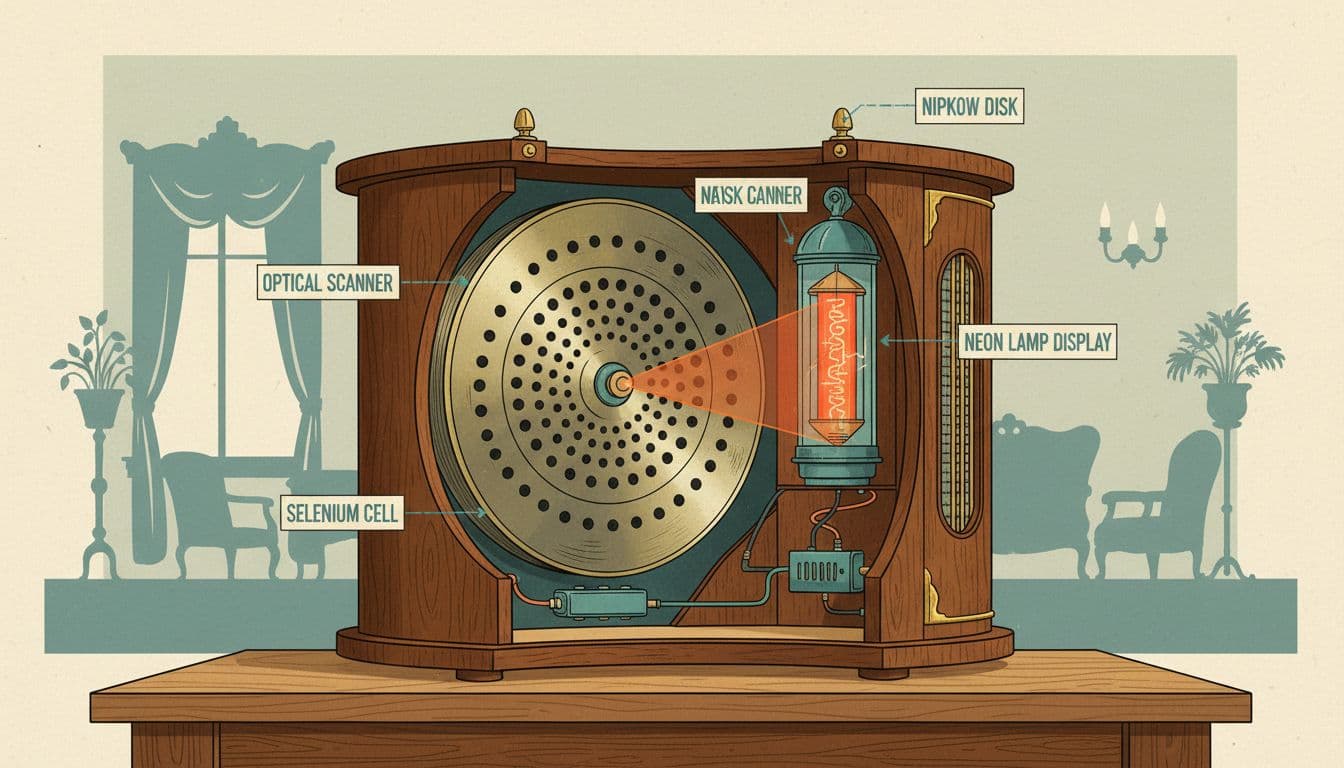

In 1884, Paul Nipkow patented a mechanical scanning disk, a way to break an image into lines and reassemble it elsewhere. The basic system depended on spinning a disk with holes arranged in a pattern. As the disk rotated, it “scanned” parts of an image in sequence. Later experimenters used related mechanical scanning methods in early television demonstrations, before electronic television systems took over. Mechanical TV could show that “seeing at a distance” was possible, but it struggled with resolution, brightness, and stability. Once electronics improved, the mechanical route became an evolutionary dead end.

Electric vehicles have a similar story, and it’s older than many people think. Battery-powered road vehicles were experimented with in the 1800s, and electric cars had a real presence in the early 1900s, especially for short trips. But batteries were heavy, range was limited, and charging was slow. Gasoline vehicles benefited from longer range and quick refueling, and fuel distribution scaled up fast.

It’s important to be careful with the earliest electric car claims because documentation varies, and some “first” stories are repeated more confidently than the records support. What isn’t disputed is the broader pattern: electric transport was credible early, then lost the mainstream fight because the supporting system (batteries, roads, charging, and cost) wasn’t strong enough.

For readers who enjoy tracking how big ideas repeatedly appear, disappear, and return under new conditions, this roundup offers more examples to compare with: revolutionary inventions lost to history.

Conclusion

Forgotten inventions aren’t magic predictions. They’re proof that timing matters as much as genius. A working prototype can still be the wrong fit for its era, and a brilliant mechanism can vanish if no one can copy it, afford it, or keep it maintained.

If there’s a takeaway worth keeping, it’s this: when a “new” technology arrives, it’s worth asking what older attempt it resembles, and what changed this time that finally made it stick.