Why the Atlantis Claim Keeps Coming Back

Atlantis is the kind of story that never stays quiet.

Every few years, the “lost city” is found again. A new map goes viral. A diver posts a blurry photo. A sharper satellite image makes the rounds. The location changes, but the excitement stays the same. It is always framed as a breakthrough and spreads fast.

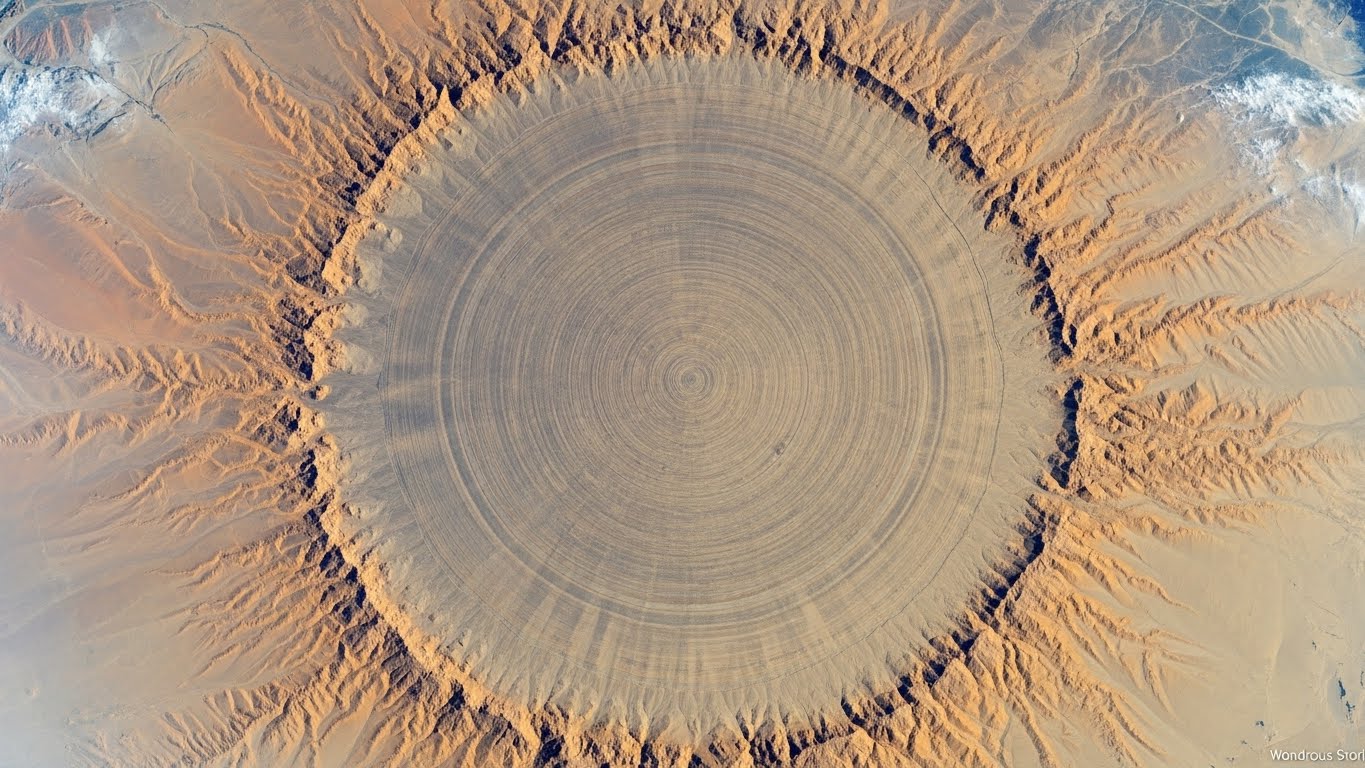

Right now, one of the most popular candidates is the Richat Structure in Mauritania, also known as the Eye of the Sahara. From space, it looks like a massive bullseye stamped into the desert. People see circular rings and imagine a city. They connect it to Plato’s famous description of Atlantis and ask a simple question: What if this is it?

A skeptical look starts with a different question: why do Atlantis claims keep coming back, even when evidence does not?

Atlantis starts with Plato, not a missing map

Atlantis does not come from an ancient travel diary or a carved monument. It comes mainly from Plato, in two works called Timaeus and Critias. In them, Plato describes a powerful island civilization that once fought Athens. Atlantis is wealthy, organized, and advanced in the ways that mattered to ancient readers: it has ports, walls, canals, temples, and a planned capital city.

Plato also gives the detail that fuels most modern comparisons: the capital city is built in concentric rings of land and water, arranged like a target.

Many people hear that and assume Plato must have been describing a real place. But Plato was a philosopher. He wrote dialogues to explore ideas. Atlantis fits neatly into a moral storyline about ambition, corruption, and collapse.

That does not prove Atlantis is fictional, but it does change how we should treat it. A philosophical story can borrow real elements while remaining mainly symbolic. This is one reason Atlantis is so hard to pin down. It sits in a gray zone between myth and history, where certainty is hard to reach.

Modern technology gives the myth a new glow

Atlantis is also a myth that ages well. It keeps getting “updated” by whatever tools the era trusts most.

Decades ago, Atlantis was linked to ocean expeditions, sonar scans, and underwater photos. Today, it is linked to satellites. High-resolution Earth imagery is now easy to access and easy to share. It produces dramatic visuals that look scientific, even when the interpretation is shaky.

Satellite imagery is a valuable resource for archaeology. It can reveal ancient roads, buried structures, and settlement patterns. But it has limits. Satellites are great at showing shape. They are not proof of a civilization. A circular pattern can be a city, geology, or the human brain trying to make sense of a complex landscape.

That is the trap. The clearer the image, the stronger the emotional reaction, even if it shows nothing human-made.

Why the Richat Structure pulls people in

The Richat Structure sits in the Sahara and spans roughly 40 to 50 kilometers. It is made of rings. It is striking. It is famous among astronauts and geology fans because it looks so unusual from above.

Online, it is often presented as if a new satellite “revealed” Richat, but Richat has long been known. What changes is the clarity and the shareability of the images. Newer satellite views make the rings pop. And once you see them, you cannot unsee the Atlantis comparison.

People who favor the Atlantis link usually point to a few ideas:

- The rings match Plato’s ringed city layout.

- The scale feels big enough for a legendary capital.

- The Sahara was once wetter, so the region could have supported a major society.

- The site looks planned, not random.

These points are not silly. They are human. They start from an honest observation: Richat looks intentional from space.

But a skeptical approach separates “looks like” from “is.”

The boring explanation usually wins: geology

Most scientific explanations describe Richat as a natural geological formation shaped by uplift and long erosion. The rings appear because layers of rock have different hardness. Softer layers erode faster. Harder layers resist erosion and remain as ridges. Over time, that can create concentric ring patterns that look almost designed.

This matters because the Richat-Atlantis claim is often built on one kind of evidence: geometry.

Geometry is nothing. But it is not enough.

A real city leaves strong signals. Even if buildings collapse, people leave traces. A settlement the size and importance of Atlantis would likely leave:

- artifacts like pottery, tools, and trade goods

- hearths, charcoal, bones, and food remains

- burial sites

- clear building stone patterns

- multiple layers of human occupation in soil and sediment

Satellite images do not show these things. They can hint at where to look, but they cannot replace fieldwork.

If the core claim is “this is a lost city,” then the core need is “show the lost city.”

Why debunking does not end the story

You might think a lack of ruins would end the debate. It rarely does. Atlantis theories often persist because the stories are structured in ways that make them easy to defend against disproof.

Here are the main reasons Atlantis claims keep coming back.

1) We are wired to see patterns

Human brains are pattern engines. We see faces in clouds. We see animals in rock formations. A giant bullseye in the desert triggers the same instinct. It feels like design, even when nature can produce similar forms.

This is one reason satellite imagery is so powerful. It compresses messy terrain into simple shapes our brains can latch onto.

2) Atlantis is a moving target

A theory that can explain every problem is hard to kill.

If the site is inland, the story shifts to “coastlines changed.”

If it is not underwater, the story shifts to “it was an island in a different climate.”

If there are no ruins, the story shifts to “it was destroyed completely.”

If the dates clash, the story shifts to “Plato got the timeline wrong.”

Each of these moves might sound plausible on its own. But together they create a claim that can always bend to fit the next objection.

3) Detail feels like proof

Plato includes measurements and design details. People treat that like a blueprint. But detailed writing is not automatically factual writing. Fiction can be extremely specific. Legends can accumulate precision over time. A story can feel “too detailed to be made up” and still be made up.

4) New tech gives old ideas a fresh coat

When someone pairs Atlantis with satellite imaging, the claim sounds modern and data-driven. But the core leap often stays the same: “this looks like the story.”

Tech can strengthen good reasoning. It can also amplify weak reasoning.

5) Atlantis offers a missing chapter of history

A lot of the Atlantis belief is emotional, not academic. It is hoped that history still has a giant surprise left, something that makes everything more mysterious and exciting.

People like mysteries. People like lost worlds. Atlantis is both.

What “real progress” would look like

If someone wants the Richat Structure to be considered a serious Atlantis candidate, the path forward is not another viral image. It is slow work:

- targeted archaeological surveys in and around the structure

- careful excavation at promising sites

- published findings that can be reviewed

- artifacts that can be dated and tied to a human settlement

- evidence of urban planning, not just circular terrain

Until then, Richat is best described as what it clearly is: one of the most striking landforms on Earth, and a perfect canvas for a story people cannot stop retelling.

So why does Atlantis keep coming back?

Because Atlantis is not only a place. It is a powerful idea.

Plato used it to talk about human nature and political decline. Modern audiences use it to talk about hidden history and the thrill of discovery. And as imaging tools improve, the temptation grows to treat a dramatic shape as a solved mystery.

Maybe the better question is not “Where is Atlantis?” but this:

How many times will we “find” Atlantis before we admit we might be chasing a mirror, not a map?

Key Takeaway

Atlantis claims keep returning because the story is emotionally satisfying and flexible, and modern tools like satellite imagery make natural patterns feel like discoveries—while real archaeological evidence remains missing.

Questions People Ask About Atlantis “Discoveries”

These FAQs support the article on why Atlantis claims keep returning, why the Richat Structure (Eye of the Sahara) gets pulled into the story, and what real evidence would actually look like.

What is the Richat Structure (Eye of the Sahara)?

The Richat Structure is a large circular geological formation in Mauritania that looks like a bullseye from space. It’s famous because the ring pattern appears intentional, even though it’s explained by natural geology.

Why do people connect the Richat Structure to Atlantis?

Plato describes Atlantis with a capital city built in concentric rings. Richat also shows concentric rings from above, so people draw a visual link and treat the shape as a clue. The image feels like a “match,” even without ruins.

Did Plato mean Atlantis as a real place or a moral story?

Plato presents Atlantis in dialogues (Timaeus and Critias) and uses it to explore politics, virtue, and collapse. That doesn’t automatically prove it’s fictional, but it does mean we should treat it like a philosophical narrative, not a straightforward historical report.

What do scientists say the Richat Structure really is?

The mainstream scientific view is that Richat is a natural formation shaped by uplift and long erosion. Different rock layers erode at different rates, creating ring-like ridges that can look “designed” from above.

If Atlantis were real, what evidence would archaeologists expect?

A large city usually leaves physical traces: pottery, tools, food remains, burials, building foundations, and clear settlement layers in soil. Big claims need fieldwork and datable artifacts, not just a compelling shape.

Why does satellite imagery make Atlantis claims spread faster?

Satellite images look authoritative and dramatic, so interpretations can feel scientific even when they’re speculative. Satellites show shape very well, but they can’t prove a civilization existed without ground evidence.

Why do Atlantis theories survive debunking?

Atlantis claims often shift to fit objections: coastlines changed, dates changed, ruins vanished, the story was mistranslated. That flexibility makes the theory hard to finish off, even when the evidence stays thin.

What would “real progress” look like for the Richat-Atlantis idea?

It would look like targeted surveys, excavation, published findings, and datable artifacts showing urban planning. Viral images don’t move the claim forward. Documented archaeology does.